For decades, joining metal—especially aluminum—meant one thing: melting it. Traditional fusion welding (like MIG or TIG) has always been a battle against distortion, cracks, and defects. The intense heat, often exceeding 3,000°C, creates a wide, weakened “heat-affected zone” (HAZ) where high-strength alloys can lose up to 50% of their original properties. This process also introduces porosity (bubbles) and solidification cracks as the molten metal cools. But what if you could forge two pieces of metal together, as if they were a single solid block, without ever reaching the melting point? This revolutionary “solid-state” solution exists, and it’s called Friction Stir Welding (FSW).

Friction Stir Welding (FSW) is a solid-state joining process that uses a non-consumable rotating tool to mechanically stir and forge two workpieces together without melting them. The tool generates frictional heat to soften the material, creating a high-strength, low-distortion weld. It is ideal for joining aluminum alloys and other materials difficult to fusion weld.

This comprehensive guide will explore the step-by-step FSW process, its significant advantages (like achieving over 90% joint efficiency), and its key applications in industries like aerospace, automotive, and high-performance electronics cooling. We will also clarify the critical differences between FSW and other “friction welding” techniques, giving you the expert knowledge to decide if this technology is right for your most demanding projects.

What is Friction Stir Welding (FSW)?

Friction Stir Welding (FSW) is a solid-state joining method, which means it joins metals without reaching their melting point. This is fundamentally different from traditional fusion welding. Instead of melting the metal, FSW uses a unique tool to create intense friction, softening the material into a plastic-like state. The tool then mechanically “stirs” these softened materials together, creating a forged, solid-state bond that is often stronger and more reliable than the original metal itself.

The Anatomy of the FSW Tool: Pin and Shoulder

The magic of FSW comes from its specially designed, non-consumable tool. This tool, typically made of a super-hard material like tool steel, has two distinct parts that perform critical jobs:

- The Pin (or Probe): This is the protruding feature at the end of the tool. The pin is responsible for plunging into the material, stirring it, and creating the “nugget” of the weld.

- The Shoulder: This is the flat, rotating surface of the tool that sits above the pin. The shoulder’s primary job is to generate the majority of the frictional heat (often 80-90%) as it rubs against the top surface of the workpieces. It also provides a crucial “forging” pressure that contains the plasticized material and smooths the top of the weld.

Key Terminology: Weld Nugget (Stir Zone), Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ), and Thermo-Mechanically Affected Zone (TMAZ)

A cross-section of an FSW weld reveals several distinct zones, which are very different from a traditional fusion weld:

- Weld Nugget (Stir Zone): The central, recrystallized area where the tool’s pin directly stirred the material. This zone has a very fine, forged grain structure, which is what gives the weld its high strength.

- Thermo-Mechanically Affected Zone (TMAZ): The area directly outside the nugget, where the material was deformed and heated by the stirring action but not fully recrystallized.

- Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ): The outermost region, where the material was heated by friction but not deformed. A key advantage of FSW is that this HAZ is significantly smaller and less weakened than the HAZ in a fusion weld.

The FSW Machine (The “Friction Stir Welder”)

A “friction stir welder” is the machine that performs the process. Unlike a simple hand-held welder, an FSW machine is a heavy-duty, precision piece of equipment. It resembles a large CNC mill, and its key components are:

- A powerful, high-load spindle to rotate the tool.

- A CNC gantry to move the tool precisely along the weld seam.

- A system for applying immense downward forging force (often several tons).

- A rigid clamping system to hold the workpieces perfectly still.

The FSW Process: A Step-by-Step Visual Guide

The Friction Stir Welding process is a precisely controlled sequence of events. While it may look like a simple spinning tool moving along a seam, it’s a sophisticated four-step dance of heat, pressure, and mechanical stirring. This process is fully automated, repeatable, and results in a near-perfect weld every time.

Step 1: Plunge

The process begins with the two workpieces securely clamped side-by-side. The FSW tool is positioned over the start of the joint line and begins to rotate at a high speed, typically between 500 and 1500 RPM (Revolutions Per Minute). The rotating tool is then slowly plunged into the material, with the pin penetrating the joint line and the shoulder just above the surface.

Step 2: Dwell

Once the pin is at the correct depth, the tool “dwells” (pauses its travel) for a few seconds. The rotating shoulder makes contact with the top surface of the material. This contact generates intense, localized friction, rapidly heating the material to a “plastic” state—hot enough to be soft and workable, but well below its melting point. For 6000 series aluminum, this is typically between 450-500°C (840-930°F).

Step 3: Traverse (The Welding Phase)

This is the actual “welding” step. The rotating tool begins to move along the joint line at a controlled traverse speed (e.g., 100-500 mm/min). As it moves, the tool performs three actions simultaneously:

- The front of the pin shears and scoops up the softened, plasticized material.

- The tool’s rotation and complex geometry stir this material, mixing it from the two separate pieces into a single, uniform, forged structure.

- The trailing edge of the shoulder provides a high forging pressure, consolidating the stirred material behind the pin and leaving a smooth, high-quality surface finish.

Step 4: Extraction

Once the tool has traversed the entire length of the weld, it stops moving forward, and the spindle is retracted from the material. This leaves a small, characteristic “exit hole” or “keyhole” where the pin was pulled out. In precision applications, this hole is often moved onto a “run-off tab” at the end of the part, which is then machined off, leaving a perfectly sealed, continuous weld.

| Parameter | Typical Range (for Aluminum) | Role in Weld Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Tool Rotational Speed (RPM) | 500 – 2000 RPM | Primary control for frictional heat generation. |

| Traverse Speed (mm/min) | 100 – 1000 mm/min | Controls heat input per unit length; faster = cooler weld. |

| Plunge Depth (mm) | Varies (e.g., 0.1 – 0.2 mm) | Ensures the shoulder generates forging pressure. |

| Tool Tilt Angle (degrees) | 1 – 3 degrees | Helps forge material down and ensures good consolidation. |

FSW vs. Traditional Fusion Welding: A Superior Bond

Friction Stir Welding is fundamentally superior to traditional fusion welding (like MIG or TIG) in almost every measurable way, especially for aluminum. This is not an opinion; it’s a matter of metallurgy. The core difference is that FSW joins metal in a solid state (a forge), while fusion welding joins it in a liquid state (a cast). And in metallurgy, a forged material is almost always stronger and more reliable than a cast one.

Why “Solid-State” is Better than “Melting” (Fusion)

This directly addresses the “how does it differ” intent. When you melt metal, you destroy its carefully engineered grain structure. As the molten weld pool cools, it solidifies just like a casting, creating a coarse, brittle grain structure. It also releases dissolved gases (like hydrogen in aluminum), which get trapped and form tiny bubbles called porosity. This creates a weak, defect-ridden joint.

FSW avoids this entirely. By never melting the metal, it simply refines the existing grain structure. The intense stirring and forging action creates a “stir zone” with a grain structure that is incredibly fine and uniform, which is the metallurgical key to high strength and ductility.

Defect Reduction: No Porosity, No Solidification Cracking

The “no melting” rule means FSW completely eliminates the most common and dangerous fusion welding defects:

- No Porosity: Since the metal never becomes liquid, gases cannot be trapped. This creates a 100% solid, void-free joint, which is critical for applications like liquid cold plates that must be perfectly leak-proof.

- No Solidification Cracking: Many high-strength aluminum alloys (like the 6000 and 7000 series used in aerospace and automotive) are considered “un-weldable” by traditional methods because they are prone to cracking as the weld pool solidifies. FSW solves this, making it possible to weld these advanced alloys with ease.

Mechanical Strength: Superior Fatigue and Tensile Properties

The results speak for themselves. A typical fusion weld on a high-strength aluminum alloy might retain only 50-60% of the base material’s original strength. A friction-stirred weld, thanks to its fine-grained forged structure, can retain 80-95% of the base material’s strength. Furthermore, the fatigue life of an FSW joint can be 2 to 10 times higher than a fusion weld, making it far more durable in applications with vibration, like cars and airplanes.

Low Distortion and Residual Stress

Traditional welding pumps a massive amount of heat into a part, causing it to warp and distort as it cools. This requires costly and time-consuming post-weld straightening. FSW uses a fraction of the heat input, and it’s localized to the joint line. This results in minimal distortion, allowing for the welding of large, precision components (like battery trays) while holding tight tolerances.

No Filler, No Fumes, No Shielding Gas

FSW is a “green” and cost-effective process. It’s fully automated, requires no consumable filler wire, and uses no shielding gas (like argon). This simplifies the process, reduces variable costs, and creates a cleaner, safer work environment with no toxic fumes or arc flash.

| Feature | Friction Stir Welding (FSW) | Fusion Welding (MIG/TIG) |

|---|---|---|

| Process Type | Solid-State (Forging) | Fusion (Melting/Casting) |

| Heat Input | Low & Localized | High & Widespread |

| Filler Material Required? | No | Yes, almost always |

| Shielding Gas Required? | No | Yes (e.g., Argon) |

| Post-Weld Distortion | Minimal | High |

| Typical Defects | None (if parameters are set) | Porosity, Cracking, Undercut |

| Suitability for “Un-weldable” Alloys | Excellent | Very Poor |

FSW vs. Other Friction Welding: Clearing the Confusion

A common point of confusion for engineers is the term “friction welding.” This term is a broad category that includes several different solid-state processes. Friction Stir Welding (FSW) is the most advanced and versatile of these, but it is not the same as “inertia welding” or “rotary friction welding.” This section directly addresses those user intents, making the distinction clear. The key difference is simple: FSW uses a separate tool to stir a seam, while other friction welding methods use the parts themselves.

What is “True” Friction Welding (FRW)?

At its heart, any “friction welding” process is one that uses mechanical friction between surfaces to generate the heat needed for a weld, rather than an external source like an arc or a flame. This general category includes several distinct techniques.

Rotary and Inertia Friction Welding

These two processes are very similar to each other and are what many engineers picture when they hear “friction welding.” They are used to join round, co-axial parts, like a bar to a plate or a tube to a fitting.

- Rotary Friction Welding (RFW): One part (e.g., a bar) is held in a motor-driven chuck and spun at a constant high speed (e.g., 2,000 RPM). The other part is held stationary. The spinning part is then forced against the stationary part under high pressure, generating intense friction. Once the interface is plasticized, the rotation stops, and a final “forge” pressure is applied.

- Inertia Friction Welding (IFW): This is a refinement of RFW. Instead of a motor, the spinning part is attached to a heavy flywheel, which is spun up to a precise speed. The flywheel is then disconnected from the motor and forced against the stationary part. The stored kinetic energy in the flywheel is converted to frictional heat. This process is highly repeatable and energy-efficient.

The key takeaway is that both RFW and IFW are limited to joining axisymmetric (round) parts.

Friction Stir Welding (FSW)

FSW is fundamentally different. The workpieces are stationary (clamped to a rigid table). A separate, non-consumable tool (the pin and shoulder) is rotated and plunged into the joint. This tool then travels along the seam, stirring the material as it goes. This means FSW is not limited to round parts. It can create long, linear, or even gently curved welds on flat plates, extrusions, and complex assemblies. This versatility is what makes it applicable to products like battery trays and liquid cold plates.

| Technique | How it Works | Geometry Limitations | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friction Stir Welding (FSW) | A separate tool rotates and travels along a stationary joint. | Can weld linear or complex 2D/3D seams (butt, lap). | EV Battery Trays, Liquid Cold Plates, Aerospace Panels. |

| Rotary Friction Welding (RFW) | One workpiece rotates at a constant speed against another. | Must be axisymmetric (round parts). | Shafts, Axles, Automotive Components. |

| Inertia Friction Welding (IFW) | One workpiece attached to a flywheel spins and forges into another. | Must be axisymmetric (round parts). | Aerospace Engine Parts, Dissimilar Metal Joints. |

What are the Key Advantages and Limitations of FSW?

Friction Stir Welding is a transformative technology, but it is not a magic bullet for every manufacturing problem. Like any industrial process, it offers a powerful set of advantages alongside a specific set of practical limitations and design constraints. A successful implementation depends on leveraging its strengths while designing around its limitations. Overall, its benefits in weld quality, strength, and environmental impact are truly exceptional.

The Overwhelming Advantages (A Summary)

We’ve touched on these, but it’s powerful to see them listed together. The “why” of FSW is compelling:

- Superior Weld Quality: FSW produces a solid-state, forged weld with a fine-grain structure, completely free of common fusion defects like porosity, cracking, and voids. This results in joints with exceptional strength (often 80-95% of the base material) and high fatigue resistance.

- Joins “Un-weldable” Alloys: FSW is the preferred, and sometimes only, method for joining high-strength aerospace (7000 series) and automotive (6000 series) aluminum alloys that are prone to cracking with traditional welding.

- Joins Dissimilar Materials: The process is highly effective at joining materials with different melting points, such as aluminum to copper or aluminum to steel, enabling new design possibilities in electronics and automotive manufacturing.

- Low Distortion & Low Heat Input: The localized, low-heat process prevents the warping and distortion seen in fusion welding, making it ideal for large, flat, or precision components.

- Energy Efficient & Environmentally Friendly: FSW is a clean, quiet process. It requires no filler wire, no shielding gas, and produces no toxic fumes, arc flash, or spatter. It also consumes significantly less energy than an equivalent arc welding process.

The Practical Limitations and Design Constraints

Engineers must also be aware of the practical constraints of the FSW process:

- The “Exit Hole”: At the end of every weld pass, the tool must be retracted, leaving a small “keyhole” where the pin was. This hole must be designed for, either by placing it in a non-critical area, running the weld off onto a “tab” that is later removed, or by using a specialized retractable-pin tool.

- Rigid Clamping: FSW generates immense forces (both downward and transverse). The workpieces must be held in a robust, custom-designed fixture to prevent any movement. This fixturing represents a significant part of the initial setup cost.

- Joint Geometry: The process is best suited for butt joints and lap joints in a linear or gently curved path. It is not easily adapted for complex geometries like T-joints or corner joints in the same way traditional welding is.

- Initial Capital Cost: FSW machines are specialized, high-load CNC platforms. Their initial investment cost is significantly higher than that of a standard MIG or TIG welding robot, making it a technology for serious, high-value production.

Applications of Friction Stir Welding

Friction Stir Welding is the enabling technology behind some of the world’s most advanced products, particularly in industries that depend on lightweight, high-strength aluminum structures. Its unique ability to create perfectly sealed, distortion-free, and immensely strong joints has made it the gold standard in aerospace, automotive, electronics cooling, and more. Where traditional welding fails, FSW provides the solution.

Aerospace: The Driving Force

FSW was originally invented and patented by The Welding Institute (TWI) in 1991 for the aerospace industry, which was struggling to weld lightweight aluminum-lithium alloys. Its first major use was on the Space Shuttle’s external fuel tanks, where it replaced fusion welding to produce stronger, lighter, and more reliable tanks. Today, it is routinely used for:

- Fuselage and wing-skin panels (e.g., on the Airbus A380).

- Large cryogenic fuel tanks for rockets (e.g., SpaceX’s Starship, ULA’s Vulcan).

- Structural components that require high fatigue life.

In this industry, the weight savings and reliability gains (estimated at over $1.5 million in launch cost savings per mission for some rockets) far outweigh the initial tooling costs.

Automotive & Electric Vehicles (EV): The High-Volume Revolution

The EV industry’s massive push for lightweighting has made FSW an essential high-volume manufacturing tool. Its two primary applications are:

- EV Battery Trays: This is a core Walmate Thermal application. The battery tray is a large, flat enclosure made of aluminum extrusions that must be 100% leak-proof (IP67 or higher) and structurally rigid. FSW is the only process that can join the extrusions and seal the enclosure with minimal distortion and guaranteed, permanent, void-free welds.

- Motor Housings & Chassis Components: FSW is used to join aluminum castings to extrusions, creating hybrid chassis components and liquid-cooled motor housings that are lighter and stronger than traditional parts.

Electronics Cooling: The Leak-Proof Guarantee

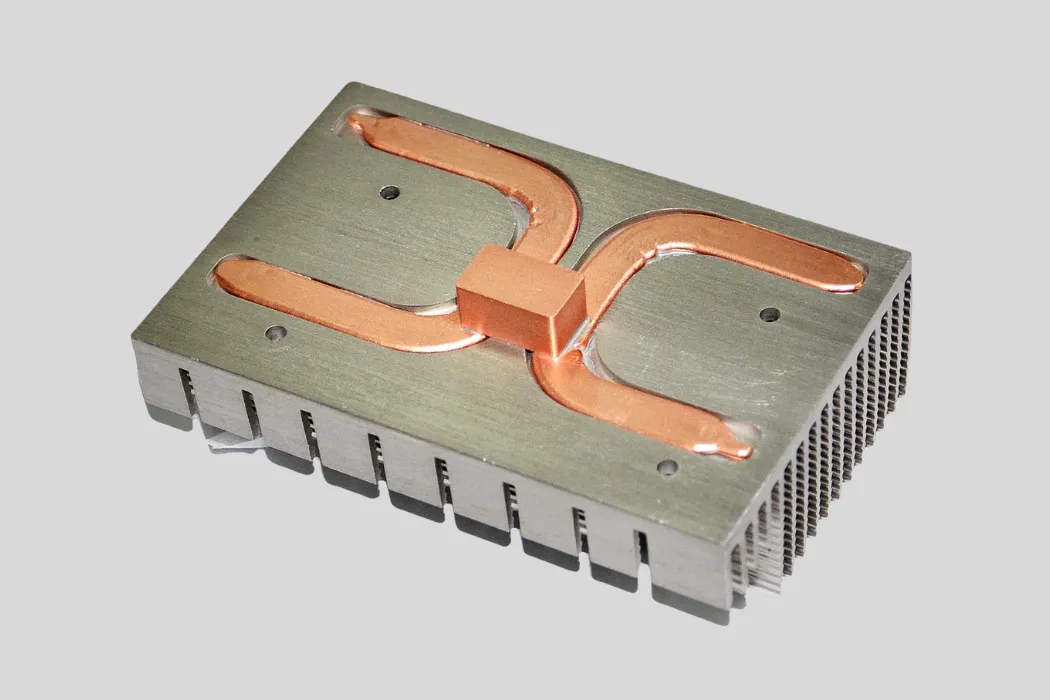

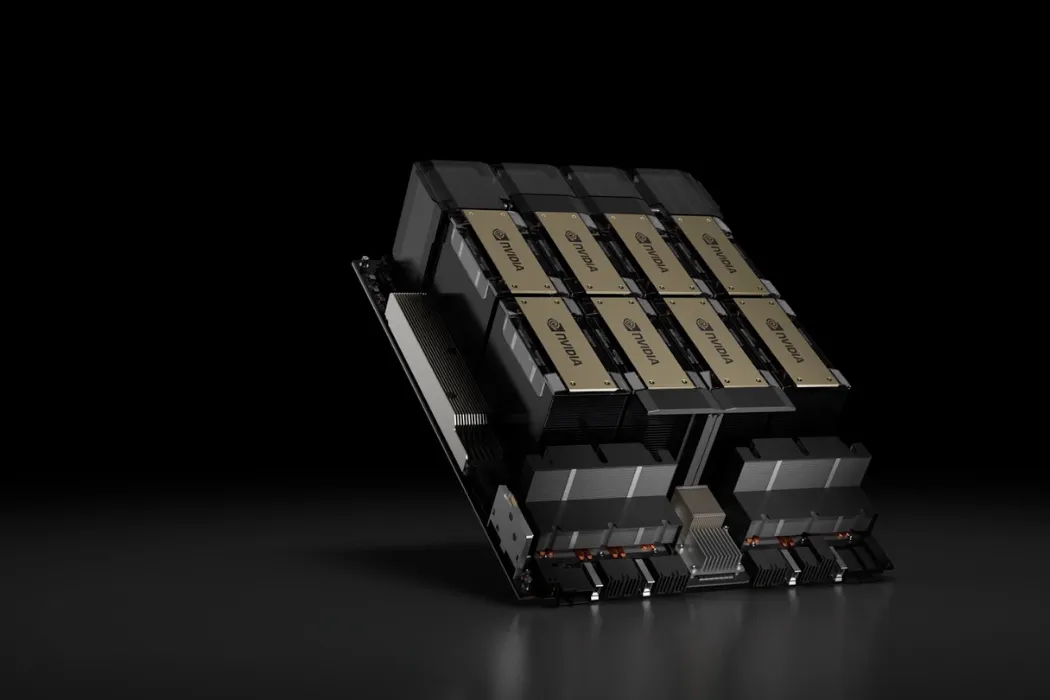

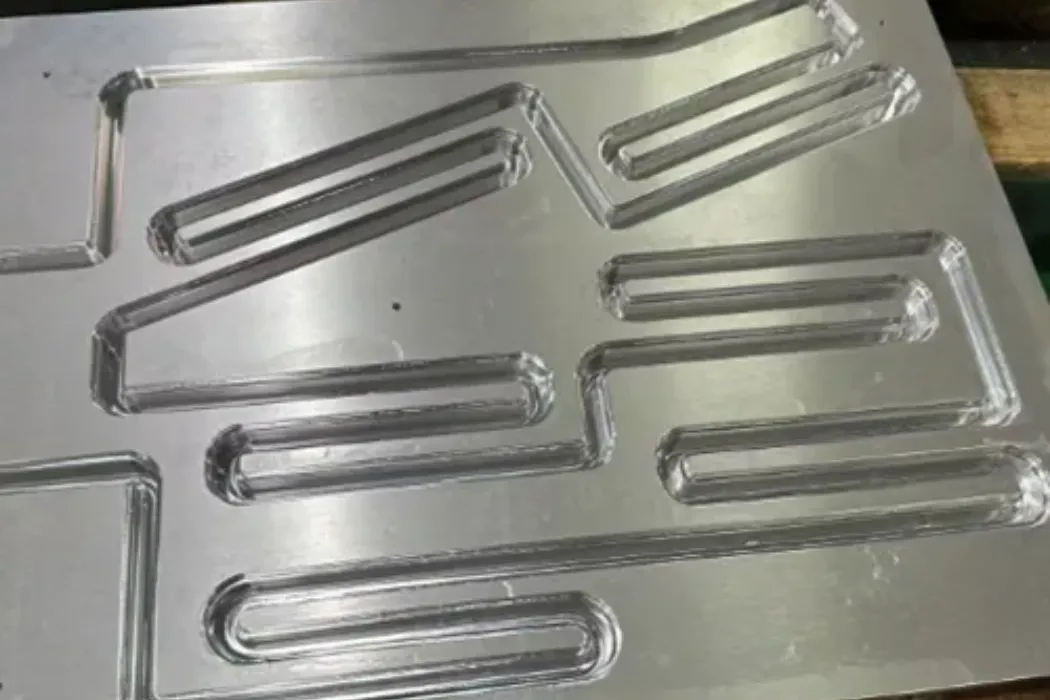

This is the killer application for FSW in high-performance electronics. As power densities in CPUs, GPUs, and power electronics have soared, liquid cooling has become essential. But liquid cooling near high-voltage electronics requires an absolute, 100% guarantee against leaks for the life of the product (10+ years).

FSW is used to manufacture high-performance liquid cold plates. A complex micro-channel pattern is machined into an aluminum or copper base, and a lid is then sealed on top. Using FSW for this final seal creates a monolithic, forged bond that is far more reliable and thermally efficient than brazing or epoxy. This is a key technology Walmate Thermal uses to produce mission-critical cooling solutions.

Marine and Rail

FSW is ideal for building large, flat, and strong aluminum panels for transportation. In the marine industry, it’s used to build the decks and hulls of high-speed ferries and naval vessels, where its low-distortion and high-strength properties are ideal for long aluminum extrusions. In the rail industry, it is used to manufacture the lightweight aluminum bodies of high-speed trains, reducing weight and increasing energy efficiency.

| Industry | Key Application | Material | Why FSW is Chosen (Key Benefit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace | Rocket Fuel Tanks, Fuselage | Al-Li Alloys, 7000 Series Al | Highest Strength-to-Weight, Defect-Free |

| Automotive (EV) | Battery Trays, Motor Housings | 6000 Series Aluminum | 100% Leak-Proof, Low Distortion, High Volume |

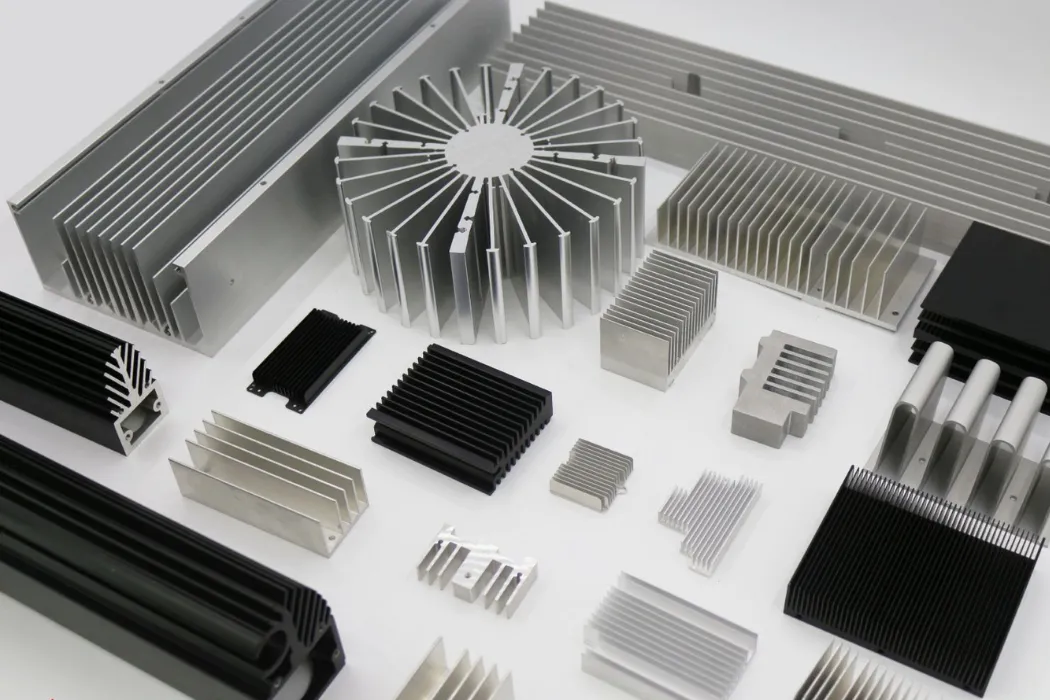

| Electronics Cooling | Liquid Cold Plates, Heat Sinks | Aluminum (6061), Copper | 100% Leak-Proof, Void-Free, Joins Al-Cu |

| Marine | Ship Decks, Hull Panels | 5000/6000 Series Al | Long Welds, Low Distortion, Corrosion Resistant |

| Rail | High-Speed Train Bodies | 6000 Series Al Extrusions | Lightweight, High Fatigue Strength |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the main difference between friction stir welding and friction welding?

The main difference is the tool and the part movement. “Friction Welding” (like rotary or inertia) spins one entire workpiece against another to join them, usually for round parts. Friction Stir Welding (FSW) uses a separate, non-consumable tool that travels along a stationary joint (like a seam).

2. Why is FSW so effective for welding aluminum?

Because it’s a solid-state process. It joins aluminum below its melting point (around 450-500°C), which completely prevents defects like porosity (gas bubbles) and solidification cracking that plague traditional fusion welding of aluminum alloys (like the 6000 and 7000 series).

3. What is the “stir zone” in an FSW weld?

The “stir zone,” or weld nugget, is the central, recrystallized area of the weld where the tool’s pin has directly stirred the plasticized material together. This zone has a very fine, forged grain structure, which is what gives the weld its exceptional strength and ductility.

4. Can FSW be used to join dissimilar materials, like aluminum and copper?

Yes, this is one of its most powerful capabilities. FSW is extremely effective at joining dissimilar materials that cannot be fusion welded, such as aluminum to copper (a key application for high-performance electronics) or aluminum to steel. Walmate Thermal uses this capability to create advanced thermal solutions.

5. Is FSW an expensive welding process?

The initial capital cost for an FSW machine is high, which can make it seem expensive. However, for high-volume manufacturing, it is often cheaper than traditional welding because it requires no filler wire, no shielding gas, and produces a high-quality, repeatable weld with fewer defects and less post-weld processing.

6. How does FSW create a 100% leak-proof seal for liquid cold plates?

FSW creates a monolithic, forged bond by stirring the parent metals together. Unlike a brazed joint (which uses a separate, lower-temp filler) or an epoxy seal, an FSW joint has no “seam” in the traditional sense. It’s a continuous, void-free grain structure, making it the most reliable method for guaranteeing a 100% leak-proof seal for critical applications like liquid cold plates.

7. What are the main applications of FSW in electric vehicles?

In EVs, FSW is the gold standard for manufacturing aluminum battery trays and enclosures. Its ability to create long, distortion-free, and perfectly sealed joints is essential for protecting the batteries and ensuring the structural integrity of the vehicle’s chassis.

8. Does Walmate Thermal use FSW for manufacturing its heat sinks or cold plates?

Yes. FSW is one of our core advanced manufacturing technologies. We utilize it specifically for producing high-reliability, leak-proof liquid cold plates and for joining dissimilar metals in custom thermal assemblies, ensuring the highest level of quality and performance for our clients.

Conclusion: The Future of High-Strength Joining

Friction Stir Welding is more than just an incremental improvement; it’s a proven, transformative technology that fundamentally overcomes the flaws of traditional fusion welding. By joining materials in a solid state, FSW eliminates the entire category of defects—like porosity, cracking, and distortion—that plague molten processes. It has redefined what is possible in manufacturing, proving it’s not just a “better weld” but a superior, more reliable engineering process for high-performance materials.

Its unique ability to create strong, lightweight, and defect-free joints in difficult-to-weld materials like 6000 and 7000 series aluminum alloys has made it the go-to solution for the world’s most demanding applications. Industries from aerospace, which relies on it for ~70m tall rocket fuel tanks, to high-speed rail and automotive have adopted FSW as the gold standard for achieving reliability and strength previously thought impossible in lightweight structures.

This same technology is what guarantees the performance and reliability of our most advanced thermal solutions.

When a leak is not an option, FSW is the answer. Walmate Thermal harnesses the power of Friction Stir Welding to build custom liquid cold plates and EV battery trays with unparalleled, leak-proof reliability. We use FSW to create monolithic, void-free seals that ensure the long-term integrity of your most critical systems.Contact our engineering team today to discuss your project. Let’s leverage FSW technology to build a stronger, lighter, and more reliable thermal solution for you.