In the world of electronics, silence is golden. That’s the beauty of passive cooling. A well-designed passive heat sink works tirelessly, with no moving parts, no noise, and zero power consumption. For countless applications, from consumer routers to industrial control systems, it’s the perfect, reliable solution. Engineers love it for its simplicity and “set-it-and-forget-it” nature. But as our electronics get more powerful and compact, this silent guardian is hitting a hard wall. There’s a hidden limit where this simple solution suddenly isn’t enough, and ignoring it can lead to throttling, instability, and even catastrophic failure.

The main obstacle to using passive heat sinks is **thermal saturation**. This occurs when the heat sink absorbs heat from a component faster than it can naturally dissipate it into the surrounding air. The heat sink’s temperature rises until it can no longer effectively cool the component, leading to overheating. This limit is dictated by the heat load, the ambient temperature, and the physical constraints of the heat sink’s size and design.

What happens when the heat your tiny, powerful processor generates is just too much for that block of aluminum to handle? It’s like trying to bail out a speedboat with a teaspoon. The heat sink becomes saturated, and performance plummets. This article will pull back the curtain on this exact problem. We’ll explore why thermal saturation is the arch-nemesis of passive cooling and, more importantly, show you how advanced design, smarter manufacturing, and innovative thermal technologies can help you break through this barrier.

What Exactly Defines a Passive Heat Sink?

A passive heat sink is a component that cools a device without any mechanical assistance. Think of it as a silent, stationary radiator for your electronics. Its sole job is to absorb heat from a hot component (like a CPU) and radiate it away into the surrounding air. The entire process relies on natural physics, making it incredibly simple and reliable. It’s the ultimate example of elegant, minimalist engineering in thermal management.

The Simple Mechanics of Natural Convection

A passive heat sink works primarily through a process called **natural convection**. Here’s how it unfolds:

- The heat sink’s base makes direct contact with the hot electronic component, pulling heat away via conduction.

- This heat travels up into the fins, which are designed to have a massive surface area.

- The air molecules touching the hot fins heat up, become less dense, and naturally rise.

- Cooler, denser air then flows in to take its place, creating a slow, continuous, and silent airflow cycle.

This “breathing” process requires no fans or pumps. It’s driven purely by the temperature difference between the heat sink and the air.

Anatomy of a Heat Sink

While they look simple, heat sinks have a few key parts working together:

- The Base: The flat surface that sits on the component. A perfectly smooth, flat base is crucial for good thermal contact.

- The Fins: These are the “teeth” or blades that stick out from the base. Their job is to maximize the surface area that touches the air. More surface area means faster cooling.

- Thermal Interface Material (TIM): This is a critical, often overlooked layer. It’s a paste or pad that fills the microscopic air gaps between the component and the heat sink base, ensuring efficient heat transfer. Without good TIM, even the best heat sink will perform poorly.

Passive vs. Active Cooling: A Core Distinction

The key difference is simple: moving parts. A passive heat sink has none. An **active heat sink** is essentially a passive one with a fan bolted on. This is called “forced convection.” The fan dramatically speeds up the airflow over the fins, allowing the heat sink to shed heat much faster. While more powerful, this comes at the cost of noise, power consumption, and lower reliability due to the fan’s limited lifespan.

What is the Main Obstacle Limiting Passive Heat Sinks?

The number one obstacle that limits a passive heat sink is **thermal saturation**. It’s the point where the heat sink is so full of thermal energy that it can no longer cool the component effectively. This happens because its ability to dissipate heat into the air through natural convection is finite. Once the heat coming in exceeds the heat going out, the system’s temperature spirals upwards until the component either throttles its performance or fails completely.

The Unseen Enemy: Thermal Saturation

Imagine a sponge. It can absorb water, but only up to a certain point. Once it’s saturated, any more water you pour on it just spills over. A passive heat sink behaves in much the same way with heat.

Natural convection is a relatively slow process. It depends on the gentle movement of air. If a component generates a large, concentrated burst of heat, the heat sink absorbs it quickly. However, it can’t get rid of it into the surrounding air fast enough. The fins get hot, the air around them gets hot, and the cooling process stalls. The heat sink is now “saturated,” and the temperature of the chip it’s supposed to be cooling starts to climb.

This isn’t a defect; it’s a fundamental physical limit. The efficiency of natural convection is tied directly to the temperature difference between the fins and the air, and the total surface area of the fins. When the heat load is too high, this natural process simply can’t keep up.

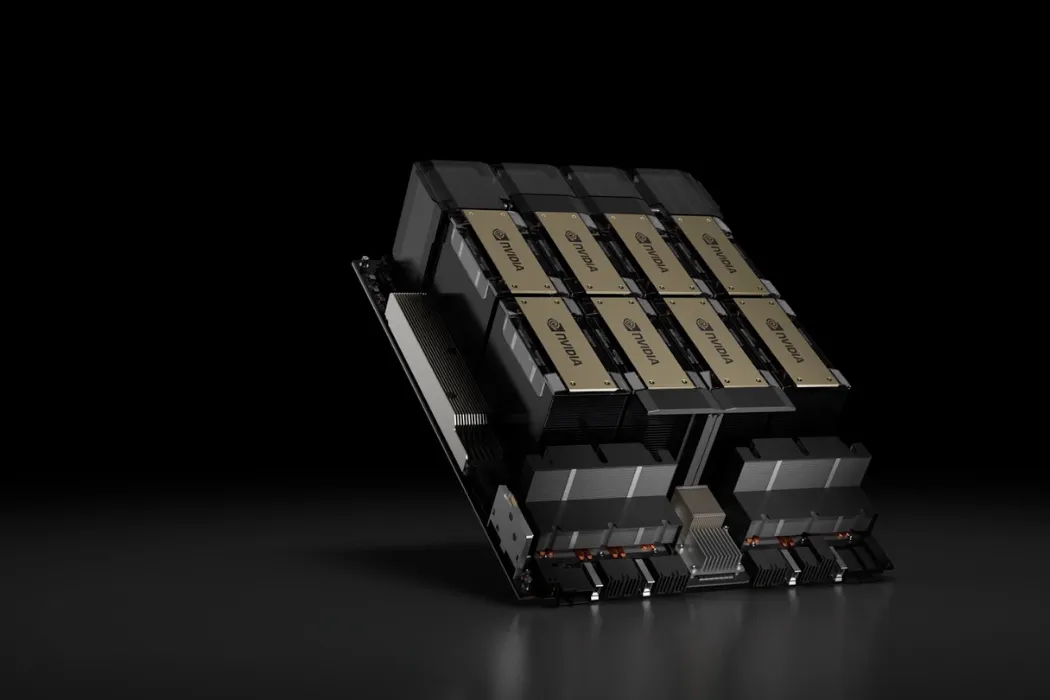

The Impact of High Thermal Design Power (TDP)

Modern electronics are the primary cause of this problem. A processor from ten years ago might have had a Thermal Design Power (TDP) of 35 watts. Today, high-performance CPUs and AI accelerators can easily exceed 150-300 watts. This is a massive amount of heat generated in a very small area. A simple block of aluminum, relying only on natural air movement, stands little chance against such a concentrated thermal load. This is why you see giant, fan-assisted coolers in gaming PCs, not simple passive blocks.

The Critical Role of Ambient Air and Enclosure

A heat sink doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Its performance is critically dependent on its environment.

- Ambient Temperature: If the air inside the device’s case is already warm (e.g., 45°C), the heat sink’s ability to cool is severely hampered. The smaller the temperature difference between the fins and the air, the slower the convection.

- Enclosure and Airflow: A cramped, sealed enclosure is a death sentence for passive cooling. Without a clear path for hot air to escape and cool air to enter, the heat sink will just circulate the same hot air, quickly becoming saturated. Proper ventilation is non-negotiable.

The Physical Barrier: Size and Space Constraints

The obvious solution might seem to be “just use a bigger heat sink!” And while a larger heat sink with more fins does have a higher capacity, this approach has practical limits. Modern devices are all about being compact. You can’t fit a massive, one-pound heat sink inside a sleek laptop, a compact network switch, or a crowded industrial control panel. Engineers are constantly fighting for every millimeter of space, making thermal management a massive design challenge.

How Do You Know When a Passive Heat Sink Isn’t Enough?

You know a passive heat sink isn’t enough when your device starts showing clear symptoms of overheating. This often manifests as unpredictable behavior, where the system works fine under light loads but becomes unstable or slow when pushed. Recognizing these signs early is key to preventing permanent hardware damage. It’s the device’s way of telling you that its cooling system is overwhelmed and can’t keep up with the heat being generated.

Recognizing the Signs of Inadequate Cooling

Overheating isn’t always a dramatic shutdown. The symptoms can be subtle at first:

- Performance Throttling: This is the most common sign. Modern processors are designed to protect themselves. When they get too hot, they automatically slow down to generate less heat. If your device feels sluggish during intensive tasks, it’s likely throttling.

- System Instability: Random crashes, freezes, or the dreaded “blue screen of death” can all be caused by components operating outside their safe temperature range.

- Reduced Component Lifespan: This is the silent killer. Even if a chip isn’t hot enough to crash, consistently running at high temperatures will degrade it over time, leading to premature failure. Heat is the number one enemy of electronic longevity.

When the Numbers Don’t Lie: Calculating Heat Load

Engineers don’t guess; they calculate. The key metric for determining if a heat sink is adequate is its **thermal resistance ($R_{th}$)**, measured in °C/W. This number tells you how many degrees Celsius the heat sink’s temperature will rise for every watt of heat it needs to dissipate.

For example, if a heat sink has a thermal resistance of 2.0 °C/W and it’s cooling a 20-watt processor, its temperature will rise 40°C above the ambient air temperature. If the air inside the case is 35°C, the heat sink will reach 75°C. You can then check if this is a safe temperature for the processor.

If the calculated temperature exceeds the component’s maximum operating limit, you know for a fact that the passive solution is not enough.

Case Study: High-Density LED Lighting and Embedded Systems

Two areas where passive cooling constantly hits its limits are modern LED lighting and compact embedded systems. High-power LEDs are incredibly efficient, but they still generate a lot of concentrated heat. Without proper cooling, their brightness fades and their color shifts. Similarly, powerful single-board computers used in robotics or IoT are packing more and more processing power into tiny footprints. In both cases, a simple extruded aluminum heat sink is often insufficient, forcing designers to look for more advanced passive or active solutions.

Can We Overcome the Obstacles of Passive Cooling with Better Design?

Yes, we can absolutely push the boundaries of passive cooling through smarter engineering and advanced manufacturing. While the laws of physics don’t change, we can dramatically improve a heat sink’s efficiency. This involves using more complex fin structures to maximize surface area, integrating advanced materials to move heat more effectively, and using powerful software to perfect the design before it’s ever built. A well-designed heat sink is far more than just a simple block of metal.

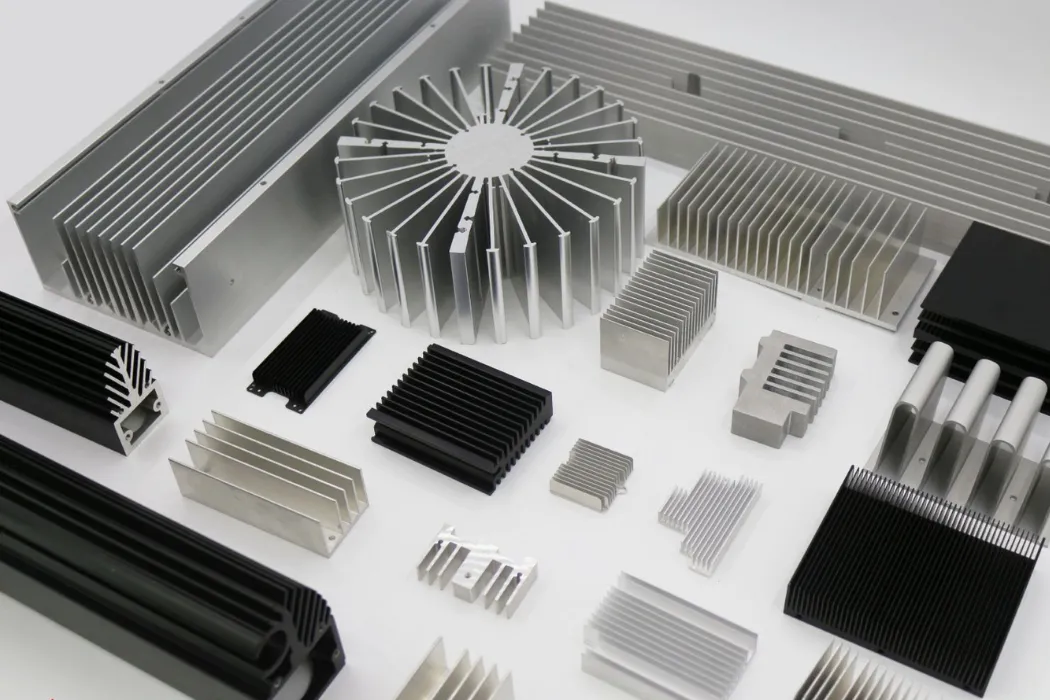

Optimizing Fin Design: The Power of Skiving and Geometry

The goal is to pack as much surface area as possible into a given volume. This is where advanced manufacturing techniques shine.

- Extruded Heat Sinks: These are the most common and cost-effective, made by pushing a block of aluminum through a die. They are good for low-power applications but have limitations on fin density and height.

- Skived Fin Heat Sinks: This is a huge leap forward. A special machine shaves ultra-thin, high-density fins from a solid block of copper or aluminum. This process, a specialty of Walmate Thermal, can create much taller and more densely packed fins, dramatically increasing surface area and thermal performance without adding significant weight or size.

The geometry of the fins also matters. Pin-fin designs, for example, are excellent in situations where airflow might come from multiple directions.

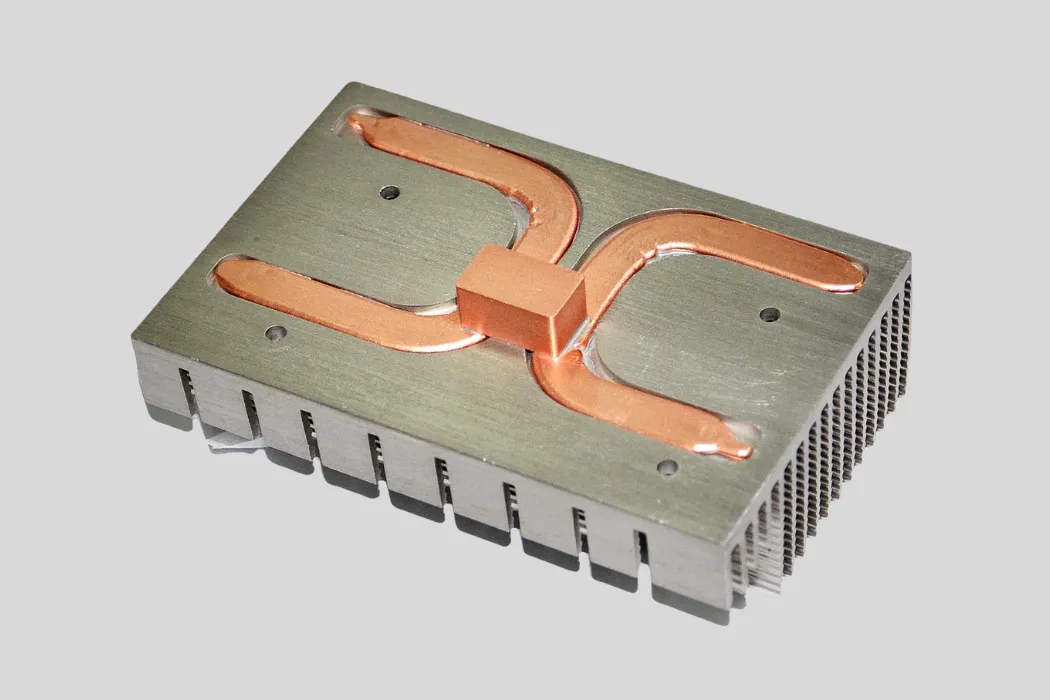

Advanced Materials and Heat Pipes

The material of the heat sink is just as important as its shape.

- Aluminum vs. Copper: Aluminum is light and cheap, but copper is a much better thermal conductor. For high-performance applications, a copper base is often used to pull heat from the source quickly.

- Heat Pipe Integration: Heat pipes are a game-changing technology. These are sealed copper tubes containing a small amount of liquid. The liquid vaporizes at the hot end (on the processor), travels instantly to the cooler end (in the fins), and condenses, releasing its heat. This process is incredibly fast and allows heat to be moved away from the source much more efficiently than solid metal alone. Walmate Thermal specializes in creating complex heat-pipe assemblies for challenging thermal problems.

The Importance of Thermal Simulation (CFD)

Modern thermal design relies heavily on **Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)** software. This allows engineers to create a virtual model of the heat sink and the entire device. They can simulate how heat will flow and how air will move, identifying potential hotspots and testing different designs digitally.

This “build it before you build it” approach, a key service offered by Walmate, saves huge amounts of time and money. It ensures the final design is optimized for performance from the very start, eliminating guesswork and costly physical prototype revisions.

Which Alternatives Should You Consider When Passive Cooling Fails?

When even the most advanced passive design isn’t enough, it’s time to consider more powerful cooling technologies. The next logical step is to add a fan for forced convection (active cooling). For the most extreme heat loads found in servers or high-power electronics, the ultimate solution is to switch to liquid cooling. Each technology offers a significant jump in cooling capacity, but also comes with its own trade-offs in terms of complexity, cost, and reliability.

The Next Step: Forced Convection (Active Cooling)

This is the most common upgrade. By simply adding a fan to a heat sink, you are no longer relying on the slow, gentle process of natural convection. The fan forces a high volume of air across the fins, carrying heat away much more rapidly. This can increase the cooling capacity of a heat sink by 3 to 5 times. It’s an effective and relatively low-cost solution, but it introduces noise, consumes power, and adds a mechanical point of failure—the fan itself.

For Maximum Power: The Shift to Liquid Cooling

When you’re dealing with hundreds or even thousands of watts of heat in a small space, even fans aren’t enough. This is where liquid cooling becomes essential. Water is over 25 times more thermally conductive than air, making it vastly superior at absorbing and transporting heat.

A typical system uses a **liquid cold plate**, a core product from Walmate Thermal, that sits directly on the hot component. A coolant is pumped through channels inside the plate, absorbing the heat and carrying it away to a radiator where it is released. This is the standard for cooling high-end gaming PCs, data center servers, and electric vehicle power systems.

Hybrid Thermal Solutions

Sometimes, the best solution is a mix of technologies. A system might use a passive heat sink for a lower-power component, a small fan for another, and a targeted liquid cold plate for the main processor. These hybrid designs allow engineers to apply the right level of cooling exactly where it’s needed, balancing performance, cost, and reliability.

| Feature | Passive Cooling | Active Cooling (Forced Air) | Liquid Cooling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max TDP Support | Low (e.g., < 40W) | Medium (e.g., 40W – 250W) | Very High (e.g., 250W – 1000W+) |

| Reliability (MTBF) | Extremely High | Limited by Fan Lifespan | High (Limited by Pump Lifespan) |

| Noise Level | Silent | Audible to Loud | Quiet to Audible |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Power Consumption | None | Low (Fan) | Low to Moderate (Pump) |

| Maintenance | None | Requires Dust Cleaning | Requires Fluid Checks/Refills |

How Are High-Performance Thermal Solutions Manufactured?

Creating a high-performance thermal solution is a precision engineering process that goes far beyond a simple block of metal. It starts with a sophisticated design and relies on advanced manufacturing techniques to achieve the complex geometries and material bonds required for top-tier performance. From skiving ultra-thin fins to brazing components together in a vacuum, every step is controlled to ensure the final product meets exact thermal specifications.

From Design to Reality: Key Manufacturing Processes

Several advanced processes are used to build the solutions we’ve discussed:

- Extrusion: The baseline for simple aluminum heat sinks. Fast and cost-effective for lower-power needs.

- Skiving: As mentioned, this technique shaves fins from a solid block, enabling much higher fin density and performance. It’s a key capability for Walmate Thermal.

- CNC Machining: For complex shapes, custom mounting patterns, or extremely flat bases, CNC milling is essential. It allows for total design freedom.

- Vacuum Brazing: This process is used to join different materials, like bonding a copper heat pipe to an aluminum heat sink or sealing a liquid cold plate. Performing this in a vacuum creates an incredibly strong, seamless joint with no voids, ensuring perfect thermal transfer.

- Friction-Stir Welding (FSW): An advanced, solid-state welding technique used for creating leak-proof seals on liquid cold plates, crucial for reliability.

Why Prototyping and Rigorous Testing Matter

A design that looks good on a computer screen must be validated in the real world. This is why prototyping is a critical step.

At Walmate Thermal, we offer rapid prototyping services to create functional samples quickly. These prototypes then undergo a battery of tests—thermal performance validation, pressure testing for liquid systems, and leak detection—to ensure they not only work but are also completely reliable and safe for the end application.

The Mark of Quality: ISO and IATF16949 Certifications

How can you trust that your cooling solution will perform consistently across thousands of units? The answer lies in certifications. Standards like **ISO 9001** ensure a company has a robust quality management system. For automotive applications, **IATF 16949** is the global standard, requiring even stricter process control and traceability.

These certifications, both held by Walmate Thermal, are not just pieces of paper. They are a guarantee to the client that every single product has been manufactured and inspected according to the highest international standards.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

1. What is the single biggest limitation of a passive heat sink?

- The biggest limitation is its finite heat dissipation rate due to reliance on slow, natural air convection. This leads to thermal saturation when dealing with high heat loads.

-

2. Can a bigger passive heat sink always solve an overheating problem?

- Not always. While a larger heat sink helps, you are often limited by physical space. Furthermore, if the enclosure has poor ventilation, even a massive heat sink will fail as it will just circulate hot air.

-

3. How does the orientation (vertical vs. horizontal) of a heat sink affect its performance?

- Orientation is critical. Fins should be oriented vertically whenever possible to allow the natural convection air current to flow upwards smoothly, like a chimney. A horizontal orientation traps air and can reduce performance by 15-25%.

-

4. Are passive heat sinks always completely silent and reliable?

- Yes. With no moving parts, they generate zero noise and have an almost infinite lifespan, making them the most reliable cooling method available.

-

5. What is thermal resistance and why is it so important for heat sinks?

- Thermal resistance (°C/W) is the primary metric of a heat sink’s performance. It tells you how many degrees its temperature will rise per watt of heat. A lower number is always better, indicating a more efficient heat sink.

-

6. At what power level (in watts) should I start considering active or liquid cooling?

- There’s no single magic number, as it depends on size and ambient temperature. However, as a general rule, once you exceed 30-40 watts in a compact space, you should seriously evaluate active cooling. For loads over 200-250 watts, liquid cooling is often the only viable option.

-

7. Do heat pipes inside a heat sink ever wear out or stop working?

- Properly manufactured heat pipes are incredibly reliable. Since they are sealed units with no moving parts, they do not wear out and are designed to last for decades, often outliving the device they are cooling.

-

8. Is a custom-designed heat sink much more expensive than an off-the-shelf one?

- While there is an initial design and tooling cost, for volume production, a custom heat sink optimized for your specific application can often be more cost-effective than using a larger, inefficient off-the-shelf part that doesn’t quite fit or perform optimally.

Conclusion: Don’t Let Heat Be Your Obstacle

The silent, simple elegance of the passive heat sink is undeniable. But as we’ve discovered, it has a clear and defined enemy: thermal saturation. The relentless march of technology, packing more power into smaller spaces, means that this physical limit is no longer an edge case—it’s a central design challenge for engineers everywhere.

Overcoming this obstacle isn’t about abandoning passive cooling. It’s about elevating it with smarter design, leveraging advanced manufacturing like skiving, integrating powerful technologies like heat pipes, and knowing when to make the strategic shift to active or liquid cooling. The difference between a good product and a great one often comes down to its thermal management strategy.

Are you facing the limits of passive cooling? Don’t let heat become your product’s bottleneck.

Walmate Thermal provides a complete, one-stop solution for your most complex thermal challenges. With over a decade of expertise, we move your project from advanced thermal simulation and rapid prototyping all the way to high-volume manufacturing of custom heat sinks, heat pipe assemblies, and high-performance liquid cold plates.Contact our engineering team today for a no-obligation quote. Let’s work together to design the perfect thermal solution and ensure your product runs cool, reliable, and performs at its absolute best.