Heat pipes are often called “thermal superconductors,” but they are not magic. Like any physical component, they have hard performance boundaries defined by fluid dynamics and thermodynamics. Ignoring these limits is the fastest way to cause a thermal failure in your system. Whether you are cooling a CPU or an automotive LED, knowing exactly where a heat pipe stops working is just as important as knowing how it works.

The limitations of heat pipes are primarily determined by three factors:

- Working Fluid Range: The freezing and boiling points (e.g., water freezes at 0°C).

- Gravity Orientation: The ability of the wick to pump liquid against gravity.

- Mechanical Constraints: The physical limits of bending radius and flattening before the wick collapses.

Exceeding these limits leads to dry-out and immediate thermal failure.

This guide provides the critical data engineers need to navigate these boundaries. We will quantify the precise limits of temperature, gravity, and mechanical deformation, helping you design reliable thermal solutions that work within the laws of physics.

What Determines the Operating Temperature Range?

The operating temperature range of a heat pipe is strictly dictated by the thermodynamic properties of its working fluid. For the standard copper/water heat pipes used in over 90% of electronics cooling, the useful operating range is typically 30°C to 200°C. Operating outside this window triggers physical phase changes that stop the heat pipe from functioning.

The Freezing Point Challenge

Water, the most efficient working fluid for electronics, hits a hard physical limit at 0°C. Below this temperature, several critical failure modes occur:

- Loss of Function: The water freezes into ice, stopping the vaporization/condensation cycle. The heat pipe becomes a passive solid copper rod with a thermal conductivity of only ~400 W/m·K.

- Volumetric Expansion: Water expands by approximately 9% upon freezing. This can deform the wick structure or bulb the tube walls.

- Reliability Risk: While copper is ductile, repeated freeze/thaw cycles can fatigue the envelope, leading to micro-cracks and eventual vacuum loss.

For sub-zero applications (e.g., outdoor telecom), alternative fluids like Methanol (freezing point -97°C) or Ammonia are required.

The Boiling Point & Internal Pressure

On the high-temperature end, the limit is defined by the structural integrity of the copper vessel against internal vapor pressure. As temperature rises, pressure escalates exponentially:

- At 100°C: Internal pressure is 1 atm (14.7 psi).

- At 200°C: Pressure jumps to roughly 15.5 bar (225 psi).

- At 250°C: Pressure exceeds 39 bar (576 psi).

Standard copper heat pipes can survive short-term reflow soldering at 260°C, but continuous operation above 200°C risks deformation or rupture. For higher temperatures, Monel/Water or Copper/Napthalene systems are necessary.

| Working Fluid | Melting Point (°C) | Useful Range (°C) | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 0°C | 30°C to 200°C | Electronics, CPU/GPU Cooling |

| Methanol | -98°C | -40°C to 85°C | Outdoor Telecom, Automotive Radar |

| Ammonia | -77°C | -60°C to 100°C | Satellite/Space Thermal Control |

| Acetone | -95°C | 0°C to 120°C | Industrial Process Cooling |

How Does Gravity Affect Heat Pipe Performance?

Gravity is the invisible enemy of heat pipe performance. A heat pipe relies on capillary action to pull the liquid condensate from the condenser back to the evaporator. When the evaporator is located above the condenser (an “anti-gravity” orientation), the wick must lift the fluid against gravity. The severity of performance loss depends entirely on the wick structure type.

Sintered Powder vs. Gravity

Sintered powder wicks are the industry standard for high-performance electronics because they offer the highest capillary pumping force. This structure consists of fused metal powder that creates tiny, sponge-like pores.

- High Capillary Head: The small pore radius generates strong suction, allowing the fluid to climb vertically.

- Performance Retention: A high-quality sintered wick can retain 80% to 90% of its maximum heat transport capacity (Qmax) even in a vertical, anti-gravity orientation (-90°).

- Ideal Use Case: Mobile devices (laptops, phones) and applications where the orientation may change during use.

Grooved and Mesh Wicks

Lower-cost wick structures struggle significantly when fighting gravity due to their larger pore sizes and weaker capillary force.

- Grooved Wicks: These have very low capillary pressure. In a vertical, anti-gravity position, a grooved heat pipe can lose over 90% of its performance, essentially failing to operate. They are best used horizontally or with gravity assist.

- Wire Mesh Wicks: These offer a middle ground but still suffer in anti-gravity scenarios, typically losing 50-70% of their Qmax when vertical.

| Wick Type | Capillary Force | Performance Loss (Vertical Up) | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sintered Powder | High | Low (~10-20% loss) | High |

| Wire Mesh | Medium | High (~50-70% loss) | Medium |

| Axial Groove | Low | Severe (>90% loss) | Low |

What Are the Maximum Heat Transport Limits (Qmax)?

Every heat pipe has a finite power rating known as its Maximum Heat Transport Capacity (Qmax). This is not a suggestion; it is a physical cliff. Exceeding this limit leads to the “Capillary Limit,” where the heat load causes the working fluid to boil off at the evaporator faster than the wick’s capillary action can return liquid from the condenser. When this happens, the wick dries out, the internal cycle breaks, and the thermal resistance spikes instantly, leading to rapid component overheating.

The Capillary Limit

While there are other theoretical limits (Sonic, Entrainment, Boiling), the Capillary Limit is the primary constraint for over 95% of electronics cooling applications. It is governed by a simple balance of pressures:

- Capillary Pumping Pressure (Pc): The force the wick generates to pull liquid back.

- Total Pressure Drop: The sum of resistance from liquid flow, vapor flow, and gravity.

For the heat pipe to function, Pc must be greater than the total pressure drop. If you push too many watts (increasing flow rate) or position it against gravity (increasing resistance), the pressure drop exceeds the pumping force, and the heat pipe fails.

Diameter Matters

The diameter of the heat pipe is the single most influential factor in determining Qmax. A larger diameter provides two critical benefits:

- More Vapor Space: A wider tube reduces the velocity and resistance of the vapor flow.

- Larger Wick Volume: More wick material can transport a greater volume of liquid.

The relationship is non-linear. Moving from a 6mm to an 8mm heat pipe (a 33% increase in width) typically results in a nearly 80% increase in power handling capacity (from ~45W to ~80W). Engineers must select a diameter that offers a Qmax well above their target heat load to provide a safety margin.

| Heat Pipe Diameter | Typical Qmax (Horizontal) | Typical Qmax (Vertical Against Gravity) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 mm | ~12 Watts | ~8 Watts |

| 4 mm | ~20 Watts | ~14 Watts |

| 6 mm | ~45 Watts | ~35 Watts |

| 8 mm | ~80 Watts | ~65 Watts |

| 10 mm | ~110 Watts | ~90 Watts |

Can Heat Pipes Be Bent or Flattened Without Issues?

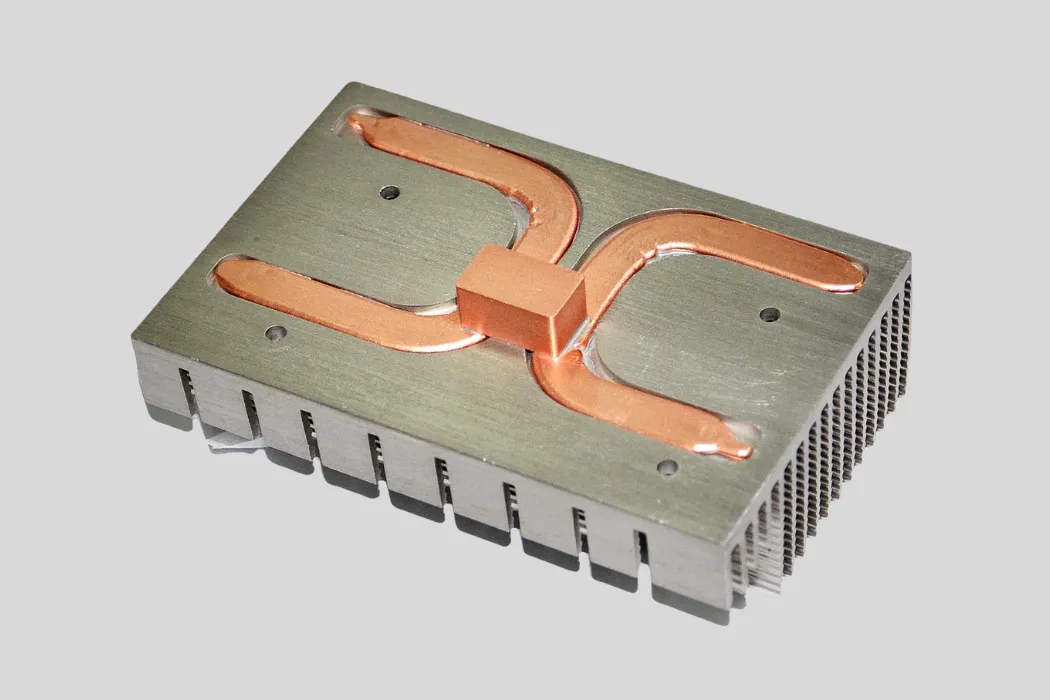

Heat pipes are prized for their flexibility, allowing engineers to route heat from a cramped PCB to a remote fin stack. However, every mechanical modification—whether bending around a capacitor or flattening to fit inside a laptop chassis—imposes a penalty. These changes reduce the internal volume available for vapor flow, increasing resistance and lowering the heat pipe’s maximum power capacity.

Bending and flattening fundamentally alter the internal geometry of the heat pipe. This constriction increases the vapor pressure drop, directly lowering the Maximum Heat Transport Capacity (Qmax). As a general engineering rule, flattening should be limited to no more than 30-40% of the original diameter (e.g., flattening a 6mm pipe to 4mm) to avoid catastrophic performance loss or wick structural collapse.

Minimum Bending Radius

Bending a heat pipe is a delicate process. Bending it too sharply can kink the copper wall or crush the internal wick structure, severing the liquid return path. To maintain reliability, follow these guidelines:

- The 3x Rule: The minimum bending radius (centerline) should generally be at least 3 times the pipe diameter. For a 6mm heat pipe, the minimum radius is 18mm.

- Tooling is Key: Precise mandrels must be used to support the tube walls during bending to prevent collapsing. Hand bending is highly discouraged for production parts.

- Wick Durability: Sintered powder wicks are more resistant to damage during bending compared to mesh or grooved wicks, which can delaminate or deform more easily.

The Cost of “Ultra-Thin”

In the race for thinner devices, engineers often flatten round heat pipes into “ultra-thin” profiles. While necessary for packaging, the thermal cost is high:

- Vapor Flow Restriction: Flattening reduces the cross-sectional area, choking the high-speed vapor flow. This is the primary cause of Qmax reduction.

- Non-Linear Loss: The performance loss is exponential, not linear. Flattening a pipe slightly (e.g., 10%) has negligible impact, but excessive flattening (e.g., >50%) can destroy thermal performance.

- Example Data: Flattening a standard 6mm heat pipe to a thickness of 2.0mm (a 66% reduction in height) effectively creates a bottleneck that can reduce its Qmax by over 50%, turning a 45W heat pipe into a 20W one.

| Original Diameter | Flattened Thickness | Thickness Reduction | Estimated Qmax Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mm | 3.0 mm | 50% | ~25-30% Loss |

| 6 mm | 2.0 mm | 67% | ~50-60% Loss |

| 8 mm | 4.0 mm | 50% | ~20-25% Loss |

| 8 mm | 2.5 mm | 69% | ~60-70% Loss |

Do Environmental Conditions Affect Reliability?

Heat pipes are hermetically sealed, passive devices, making them inherently robust. However, they are not immune to their environment. External factors such as high-frequency vibration, mechanical shock, and corrosive atmospheres can compromise their structural integrity and thermal performance. For demanding applications in automotive (EVs) and aerospace, specific design choices must be made to ensure survival.

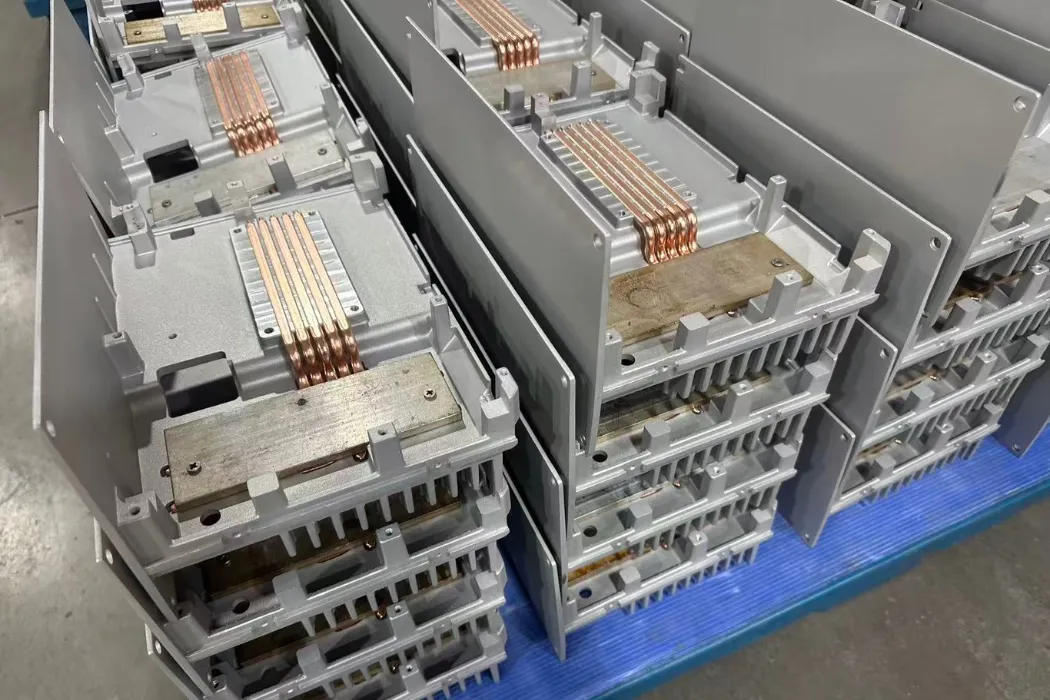

While standard heat pipes are durable, extreme conditions require specialized designs. Sintered powder wicks are mandatory for high-vibration environments because the wick is fused to the tube wall. In contrast, mesh or grooved wicks can delaminate under shock loads. Additionally, rigorous thermal cycling testing is essential to validate long-term reliability against fatigue.

Vibration and Shock

In automotive and industrial applications, heat pipes are subjected to constant vibration. This mechanical stress can be catastrophic for the wrong type of wick:

- Wick Delamination: Screen mesh wicks are held in place by tension. Under high-frequency vibration (e.g., automotive engine bay), the mesh can loosen and detach from the tube wall, severing the liquid return path and causing thermal failure.

- Sintered Durability: Sintered powder wicks are fused to the copper wall at high temperatures, creating a monolithic structure. They can withstand significant shock (often rated up to 50G) and vibration without degrading, making them the only viable choice to meet automotive standards like ISO 16750-3.

Long-Term Reliability (NCG Generation)

The primary failure mode for a heat pipe over time is not a leak, but the generation of Non-Condensable Gas (NCG), typically hydrogen. This gas creates a “bubble” at the condenser end that blocks vapor flow.

- Lifespan: High-quality heat pipes manufactured with strict cleaning processes to remove impurities typically have a lifespan exceeding 100,000 hours (over 11 years of continuous use) with minimal performance degradation.

- Altitude and Pressure: Because heat pipes are sealed pressure vessels, they are largely unaffected by external air pressure changes. A standard heat pipe operates reliably from sea level to the vacuum of space, provided the thermal interface materials (TIM) and mounting hardware are also rated for the environment.

How Do You Overcome These Limitations?

Physical limitations do not have to be dead ends for your project. They are simply engineering constraints that require smarter design strategies. When a standard heat pipe hits its thermal or mechanical ceiling, the solution lies in advanced system architecture and precision manufacturing.

Overcoming limits often means changing the geometry or the technology. If one pipe can’t handle the load, use an array. If heat flux is too high for a tube, switch to a Vapor Chamber. If the bend is too tight, use a multi-piece assembly.

Engineering Around the Limits

When a single heat pipe is insufficient, engineers have several powerful alternatives:

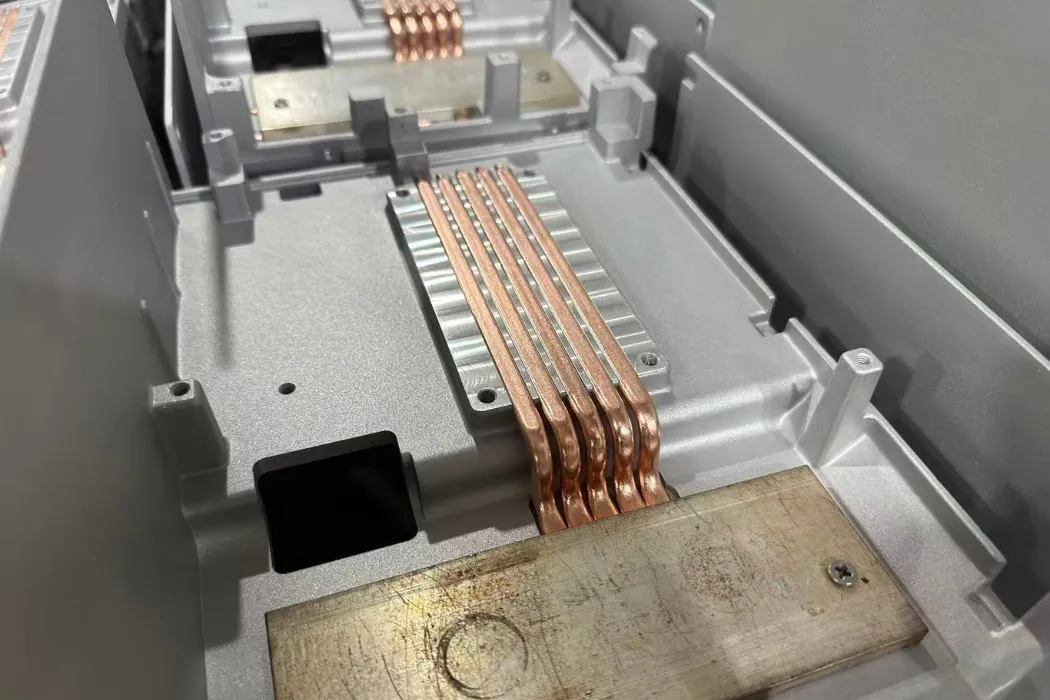

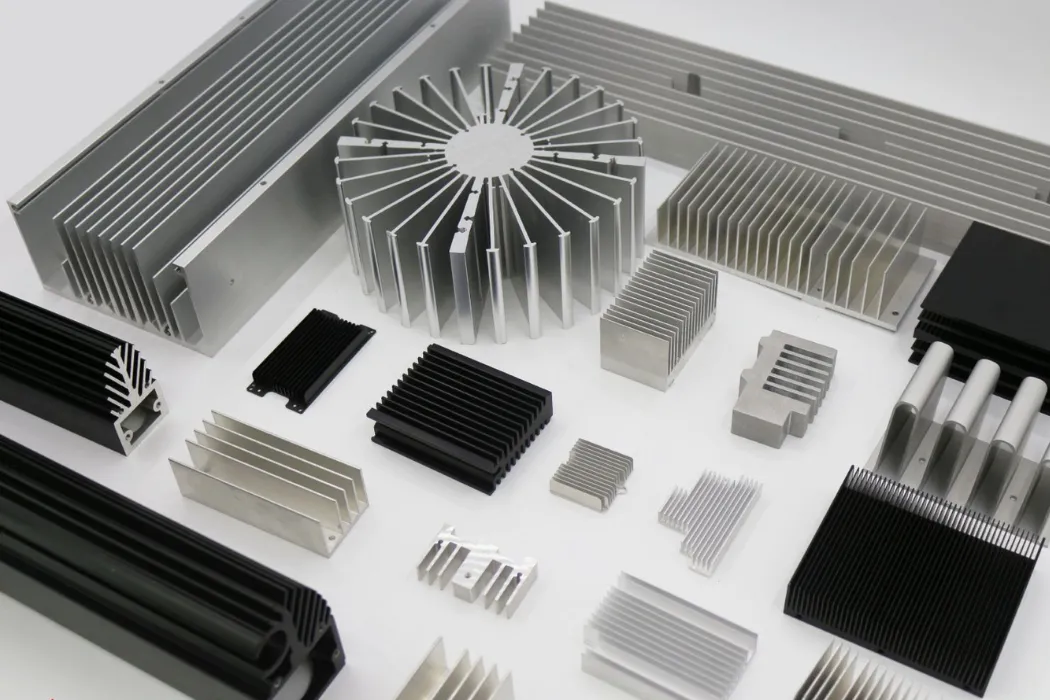

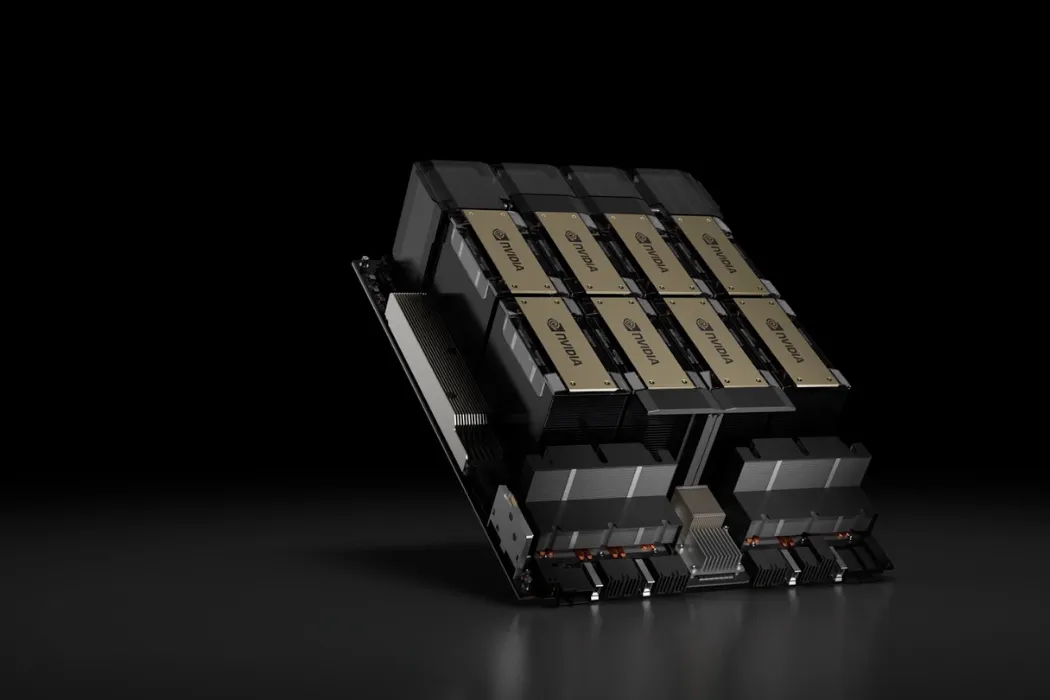

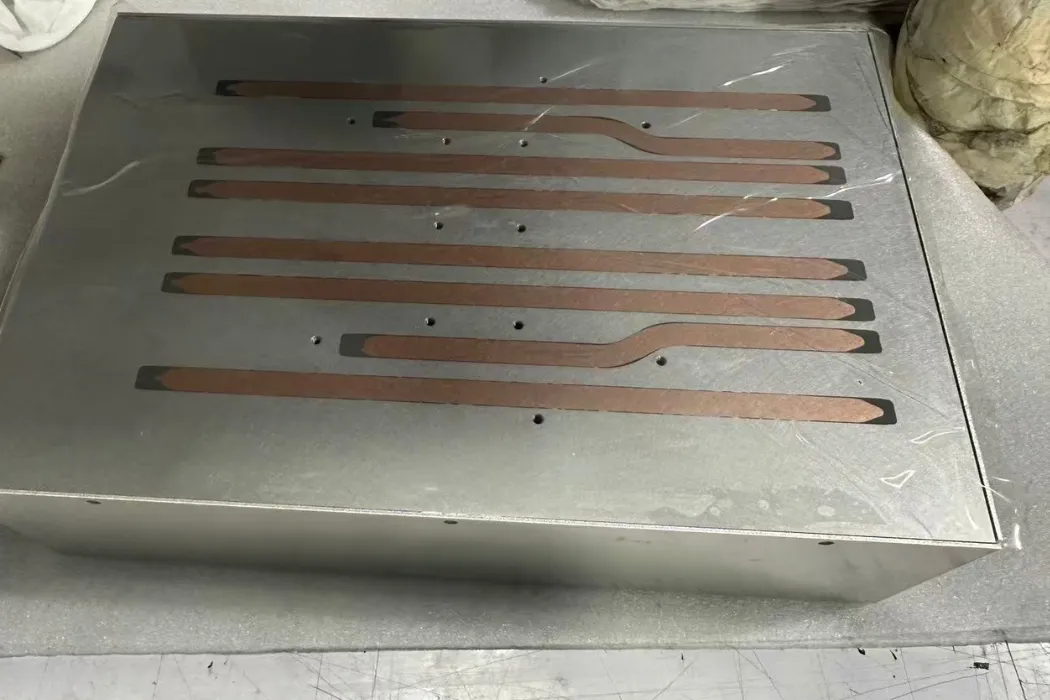

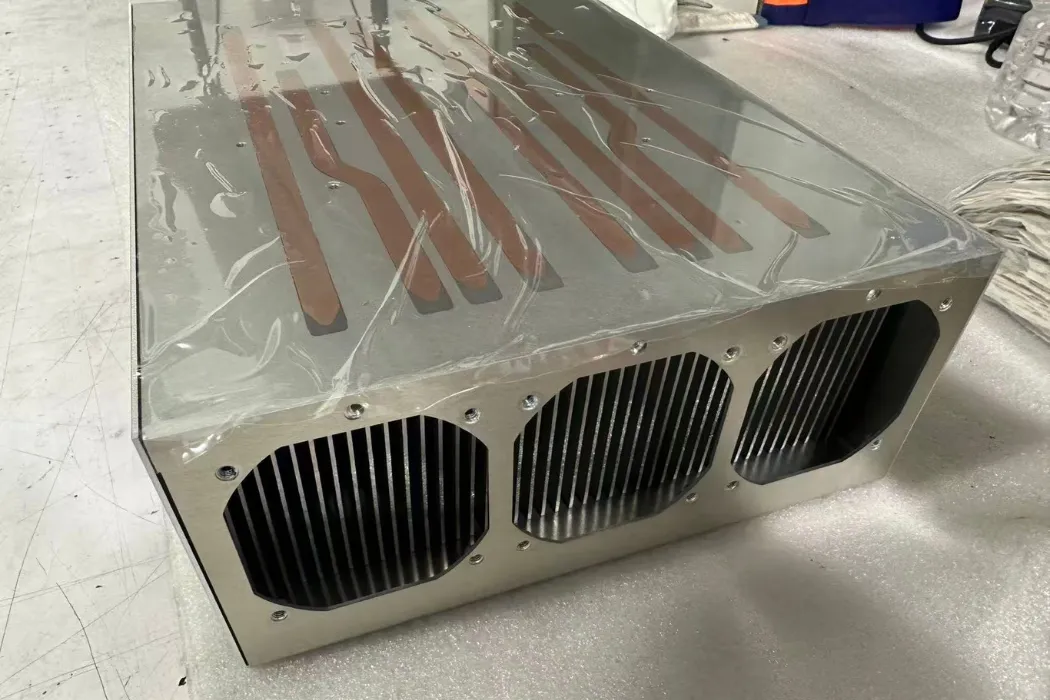

- Heat Pipe Arrays: Instead of relying on one large pipe, use multiple smaller pipes in parallel. This increases the total wick volume and surface area, linearly increasing Qmax. A CPU cooler with six 6mm pipes can handle >250W, far exceeding the limit of any single pipe.

- Vapor Chambers (Planar Heat Pipes): For high heat flux applications (e.g., >50 W/cm²), a vapor chamber is superior. It spreads heat in two dimensions (planar) rather than one (linear), effectively eliminating hot spots and overcoming the spreading resistance limits of standard flattened pipes.

- Composite Designs: If a bend radius is too tight for a heat pipe (violating the 3x rule), the design can be split. A solid copper block can be used for the tight turn, transferring heat to a straight heat pipe for the longer run.

Walmate’s Custom Solutions: Simulation Before Fabrication

The most effective way to overcome limitations is to predict them before they happen. At Walmate Thermal, we don’t guess; we simulate.

- CFD Validation: We use Computational Fluid Dynamics to model your specific heat load and gravity orientation. We can predict exactly when a wick will dry out or if a bend will cause excessive pressure drop.

- Precision Bending: We utilize CNC bending machines with internal mandrels to achieve tighter-than-standard bend radii with minimal flattening or wick damage, preserving up to 95% of the original performance.

- Custom Wick Formulas: For specific anti-gravity needs, we can customize the porosity and particle size of our sintered wicks to maximize capillary lift at the expense of some permeability, tailoring the pipe to your exact orientation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can a heat pipe freeze and burst?

Standard water-based heat pipes will freeze below 0°C, causing them to stop functioning as thermal superconductors. While water expands by ~9% upon freezing, the copper envelope is ductile enough to withstand this expansion without bursting immediately. However, repeated freeze/thaw cycles can fatigue the metal and damage the internal wick, eventually leading to failure. For sub-zero operation, fluids like Methanol are required.

2. What happens if I bend a heat pipe by hand?

Bending a heat pipe by hand without proper tooling often results in a “kink” rather than a smooth radius. This collapses the internal vapor space and crushes the wick structure. A kinked heat pipe can lose 50% to 100% of its heat transport capacity immediately. Precision CNC bending is required to maintain performance.

3. Does altitude affect heat pipe performance?

No. A heat pipe is a hermetically sealed vacuum vessel. Its internal operation depends entirely on the internal pressure of the working fluid, which is independent of the external atmospheric pressure. Heat pipes operate identically at sea level, at 40,000 feet, or in the vacuum of space.

4. Can I cut a heat pipe to size?

Absolutely not. A heat pipe relies on a partial vacuum to allow the fluid to boil at low temperatures. Cutting the pipe breaks this vacuum, allowing air to rush in. The fluid will not boil, and the device becomes nothing more than a hollow copper tube with zero thermal performance.

5. What is the lifespan of a heat pipe?

A properly manufactured heat pipe has no moving parts and nothing to wear out. The main limiter is the slow generation of non-condensable gas (NCG) over time. High-quality commercial heat pipes typically have a lifespan exceeding 100,000 hours (over 11 years) before performance degrades noticeably.

6. Can Walmate manufacture complex bent shapes?

Yes. We specialize in complex 3D bending geometries. Using advanced bending fixtures and internal support mandrels, we can achieve tight bend radii and multi-axis shapes to fit specific chassis constraints while maintaining the integrity of the internal wick structure.

Conclusion

Heat pipes are powerful thermal management tools, but they are bound by the laws of physics. Their performance is strictly defined by the operating range of their fluid, their orientation relative to gravity, and their mechanical geometry. Pushing a heat pipe beyond its freezing point, capillary limit, or bending radius will inevitably lead to thermal failure.

Successfully integrating heat pipes into a product requires more than just buying a component; it requires engineering a solution that respects these boundaries. Understanding the trade-offs between diameter, wick type, and flattening is the key to reliability.

Navigating these limits requires expert engineering.

At Walmate Thermal, we don’t just sell heat pipes; we design thermal success. We use advanced simulation and precision manufacturing to create custom heat pipe assemblies that maximize performance within your specific constraints. Whether you need to fight gravity, fit a tight enclosure, or survive extreme temperatures, we have the solution.

Contact us for a thermal analysis today. Let’s build a solution that works.