Imagine this common scenario: an engineer is designing a new device. They see the processor has a 150W TDP, so they confidently select a 150W cooler. The prototype is built, the system boots up, but under a heavy workload, performance plummets. The processor is overheating and throttling aggressively. Why? The cooler’s rating matched the TDP perfectly. This situation highlights a critical misunderstanding of one of the most important metrics in electronics: Thermal Design Power. What you think it means and what it actually means can be two very different things.

TDP, or Thermal Design Power, is a specification that represents the average amount of heat (in watts) a component like a CPU or GPU generates at its base clock frequency under a typical workload. It is primarily a guideline for thermal solution designers to create a cooler that can adequately dissipate that heat, not a measure of the component’s actual or maximum power consumption.

This guide will not only give you a clear definition of TDP but will also pull back the curtain on what it doesn’t tell you. We will explore why real-world heat generation often exceeds the official TDP, how different manufacturers like Intel and AMD define it differently, and how to use this critical metric as a starting point—not an endpoint—to engineer a thermal solution that guarantees performance, not just adequacy.

What Is TDP and What Does the “Watt” Rating Really Mean?

The “watt” rating in TDP specifies the amount of heat energy a cooling system needs to dissipate to keep a component within its optimal temperature range. It is a thermal specification, not an electrical one. Think of it as the “cooling requirement” for the processor when it’s running a typical, everyday task at its standard base speed. It is the starting point for any thermal design, defining the minimum performance a cooler must provide.

The Official Definition: A Guideline for Heat, Not Power

At its core, TDP is a simplified way for chip manufacturers (like Intel and AMD) to communicate with thermal solution manufacturers (like Walmate Thermal). It answers a single, critical question: “How much heat does your cooler need to handle?”

The “W” in a 125W TDP rating stands for watts, but in this context, it refers to thermal watts, not electrical watts. While the electricity a CPU consumes is converted into heat, TDP is specifically focused on the thermal output that needs to be managed. It is a metric created for the engineer designing the heat sink or liquid cold plate, telling them the thermal load their product must be designed to overcome.

How is TDP Measured? A Look at Base Clocks and “Typical” Workloads

This is where most of the confusion about TDP begins. The TDP value is not a worst-case scenario. It is determined under a very specific set of conditions defined by the manufacturer:

- It is measured when the processor is running at its official base clock frequency, not its higher “turbo” or “boost” frequency.

- It is measured under what is considered a “typical” or “real-world” workload, not a synthetic stress test that pushes every part of the chip to 100%.

Because of this, TDP represents a kind of “normal operating condition” thermal load. It was never intended to represent the peak heat a component could possibly generate when all its cores are running at their maximum boost speed.

Is TDP the Same as Power Consumption? A Critical Distinction

No, and this is the most important takeaway. TDP is not the same as actual power consumption. The actual power a CPU draws from your power supply can, and often will, significantly exceed its TDP rating, especially under heavy loads.

Think of it like the fuel economy rating for a car. The sticker might say it gets 30 miles per gallon, which is true under ideal highway driving conditions (the “base clock”). But if you’re racing the car up a mountain (a “boost clock” workload), your actual fuel consumption will be far higher. Similarly, a CPU will draw much more power—and generate much more heat—when it boosts its clock speeds to handle a demanding task. The TDP only tells you the cooling required for the “ideal highway drive.”

Why Does My CPU’s Power Draw Exceed its TDP? The Reality of Boost Clocks

Your CPU’s power draw exceeds its TDP because modern processors are designed to be opportunistic. They automatically increase their clock speeds far beyond the base clock—a feature called “boost” or “turbo”—to maximize performance. This boost state consumes significantly more power and generates much more heat than the TDP rating suggests. The TDP is merely the thermal guideline for the baseline speed, not for these crucial, high-performance boost speeds.

From Base Clock to Boost Clock: Where TDP Breaks Down

Modern processors are intelligent. They constantly monitor their temperature and power delivery. If the CPU detects that it is running cool enough and has sufficient power (a state known as having “thermal and power headroom”), it will automatically raise its clock speed to complete tasks faster. This is the “boost” state, and it is the primary reason why a 125W TDP processor can suddenly generate over 200W of heat.

The TDP is tied to the guaranteed base clock, but nearly all of a modern CPU’s performance advantage comes from its ability to intelligently and aggressively boost. Therefore, a cooling solution designed *only* for the TDP will force the CPU to quickly exit its high-performance boost state, effectively crippling its potential.

Understanding the Alphabet Soup: Intel’s PL1/PL2 vs. AMD’s PPT

Recognizing the limitations of TDP, both Intel and AMD have more detailed power specifications that engineers should pay close attention to. These numbers represent the *actual* power limits far more accurately than the advertised TDP.

- Intel (PL1 & PL2): Intel defines two power levels. Power Limit 1 (PL1) is the long-term, sustained power limit, which is typically equal to the official TDP. Power Limit 2 (PL2) is the much higher, short-term maximum power the CPU is allowed to draw while boosting.

- AMD (PPT): AMD uses a metric called Package Power Tracking (PPT). This value defines the maximum power that can be delivered to the CPU socket. The PPT is almost always significantly higher than the advertised TDP and represents the true peak thermal load.

| Manufacturer | Advertised Metric (TDP) | Real Power Limit (What it means) |

|---|---|---|

| Intel (e.g., Core i9-14900K) | 125W (Processor Base Power) | 253W (PL2 – Maximum Turbo Power) |

| AMD (e.g., Ryzen 9 7950X) | 170W | 230W (PPT – Package Power Tracking) |

So, Is TDP Just a Marketing Number?

It’s not *just* a marketing number, but its role has changed. In the past, TDP was a more reliable engineering figure. Today, it is better understood as a **classification tool or a “T-shirt size”** for coolers and systems. It helps categorize processors into broad thermal families (e.g., a “65W” class chip vs. a “125W” class chip).

For a thermal engineer, TDP should be seen as the absolute minimum requirement—the starting point of a conversation. A truly effective thermal solution must be designed not for the TDP, but for the much higher PL2 or PPT values, where the processor’s real performance lies.

How Does TDP Affect Different Types of Electronics?

TDP is not a universal constant; its importance and interpretation change dramatically depending on the application. For a high-performance gaming desktop, a high TDP is often a badge of honor, signaling immense processing power. For a thin-and-light laptop, a low TDP is a strict boundary that dictates the balance between performance and battery life. And in industrial systems, TDP is a baseline to be managed for ensuring long-term reliability above all else.

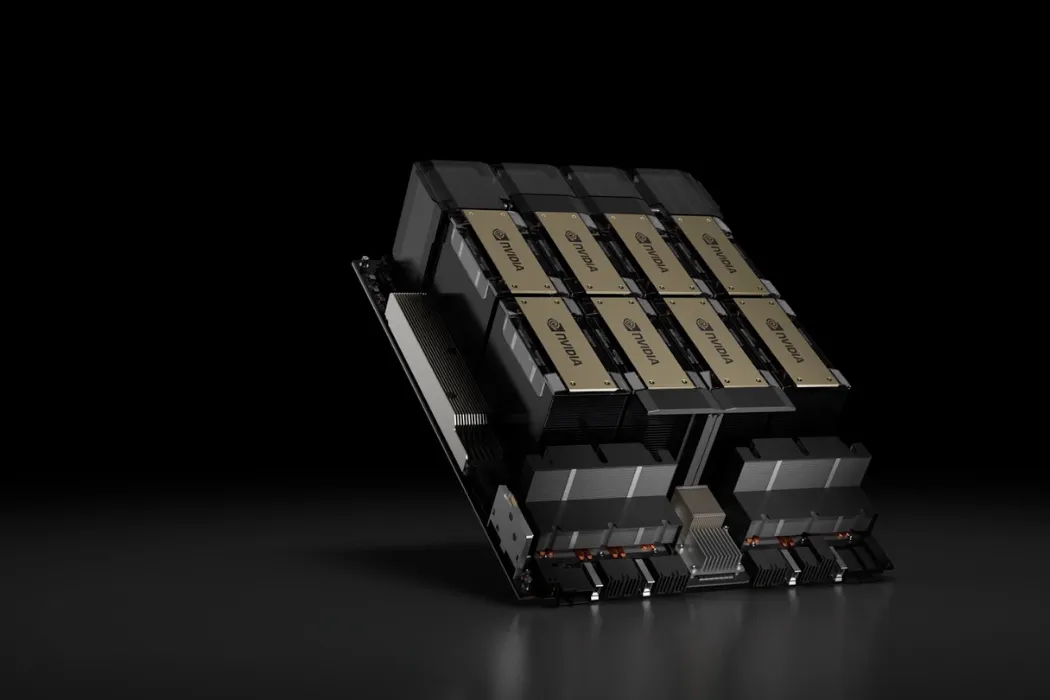

For Desktop CPUs & GPUs: The Battle for Performance

In the world of high-end desktops and workstations, performance is king. Here, a high TDP is directly correlated with higher potential performance. A 170W TDP processor is fundamentally more capable than a 65W one because it is designed to handle more electricity and, therefore, more heat. This allows it to sustain higher boost clocks for longer periods.

However, this performance comes at a cost: it demands a robust thermal solution. This is the primary market for large air coolers and advanced liquid cooling systems. The goal of the cooling solution is to create enough thermal headroom to allow the CPU or GPU to stay in its high-power boost state (PL2 or PPT) for as long as possible, maximizing the performance the user paid for.

For Laptops & Mobile Devices: The Constraint of a “TDP Envelope”

In thermally constrained devices like laptops, tablets, and handhelds, the dynamic is completely different. The physical size of the chassis and its limited ability to dissipate heat create a strict “TDP envelope”. A processor might be capable of boosting to a high power level, but it can only do so for a few seconds before it hits its thermal limit and must throttle back down to its sustained TDP (e.g., 15W, 28W, or 45W).

This is why a laptop “Core i7” performs very differently from a desktop “Core i7,” even if they share a name. The laptop’s performance is entirely dictated by its cooling system’s ability to manage the heat within that tight TDP envelope. The engineering challenge here is maximizing efficiency and heat removal within an incredibly small space.

For Industrial & Embedded Systems: Reliability Over Speed

In industrial control systems, medical equipment, or aerospace applications, the top priority is not squeezing out the last drop of performance. It is absolute, unwavering reliability over a long operational life, often in harsh environments with high ambient temperatures.

For these mission-critical applications, engineers often take a conservative approach. They might select a 95W TDP processor but design the system and its thermal solution to ensure it rarely, if ever, exceeds a 65W thermal load. By intentionally running the component well below its rated TDP, they reduce thermal stress on the silicon, significantly extending its lifespan and ensuring predictable, stable operation for years.

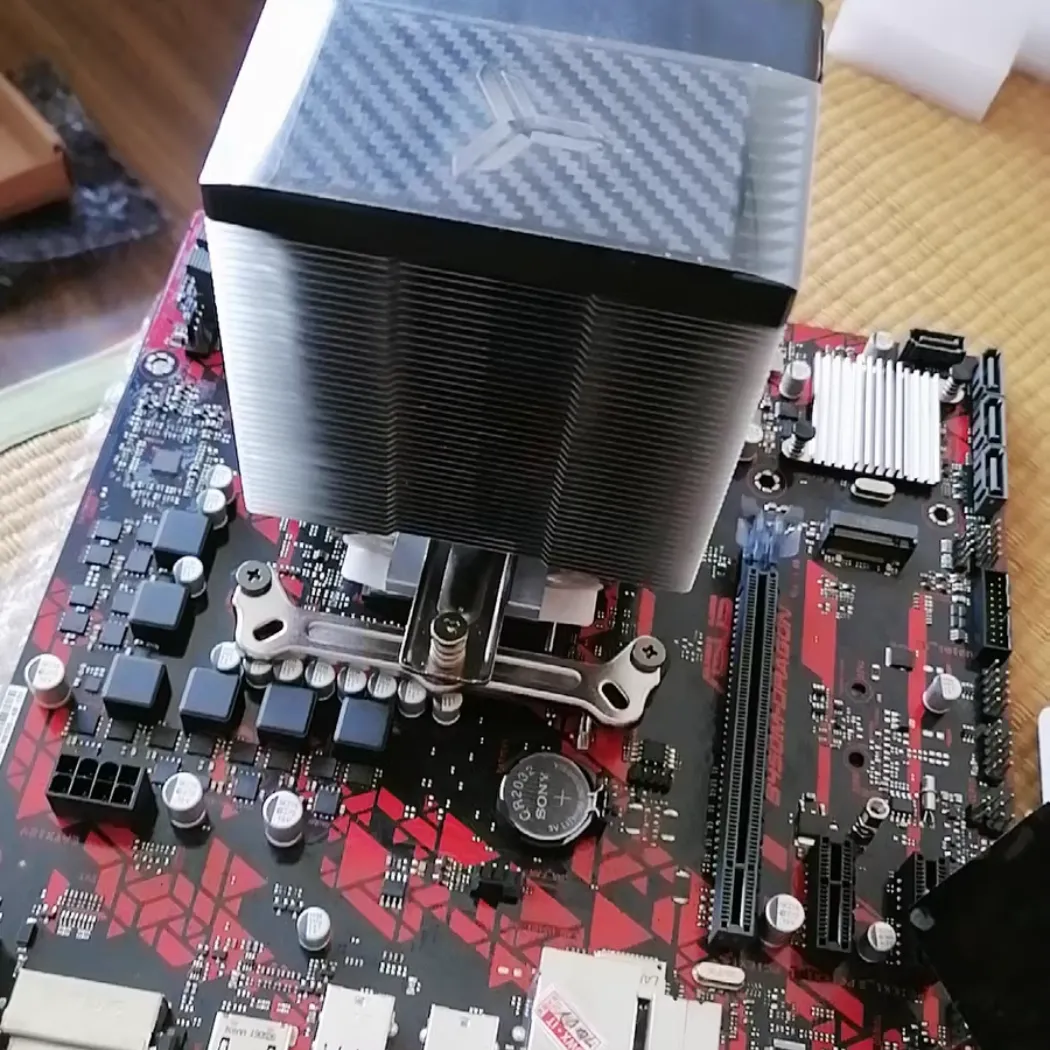

How Should Engineers Use TDP to Select a Thermal Solution?

Engineers should use TDP as a starting baseline, not a final specification. A smart thermal design process treats the official TDP as the absolute minimum requirement and then builds in a significant safety margin to handle real-world boost states and environmental factors. For any custom or mission-critical application, the process must then move beyond this simple number and rely on detailed simulation and testing to guarantee performance and reliability.

Step 1: Using TDP as a Baseline, Not a Limit

The first rule of selecting a cooler is to aim for a cooling capacity that is significantly higher than the component’s advertised TDP. Why? Because you must design for the peak thermal load (PL2 or PPT), not the average (TDP). A reliable rule of thumb is to select a thermal solution with a TDP rating at least 1.5 times higher than the processor’s TDP. For a 125W TDP chip that can boost to over 200W, you should be looking at coolers rated for 200W or more.

Choosing a cooler that only matches the TDP is a recipe for performance throttling. You are essentially leaving all the chip’s high-performance boost potential on the table.

Step 2: Accounting for Environment and Use Case

A cooler’s performance is not determined in a vacuum. TDP ratings are measured in a controlled lab environment. You must account for real-world conditions, which TDP does not cover:

- High Ambient Temperatures: Will the device operate in a hot factory or a sun-drenched vehicle? Higher ambient temperatures reduce a cooler’s effectiveness and require a more powerful solution.

- Poor Chassis Airflow: A compact, poorly ventilated enclosure will trap heat, making any thermal solution work harder. The design of the chassis is as important as the cooler itself.

- 24/7 High-Load Applications: Will the component be running intensive simulations or processing data continuously? A system under constant heavy load requires a far more robust cooling solution than one that only experiences short performance bursts.

Step 3: When to Move Beyond TDP: The Need for Simulation

For standard PC builds, using the “1.5x rule” and considering the environment is often sufficient. But for developing a custom, high-density, or mission-critical product, relying on TDP ratings is simply not good enough. The risks of thermal failure are too high.

This is the point where you must move from simple ratings to professional engineering. Thermal simulation using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) becomes essential. At Walmate Thermal, this is a core part of our service. We create a digital model of your device to analyze airflow and heat transfer, allowing us to design and validate a truly custom thermal solution that is guaranteed to meet your specific performance targets.

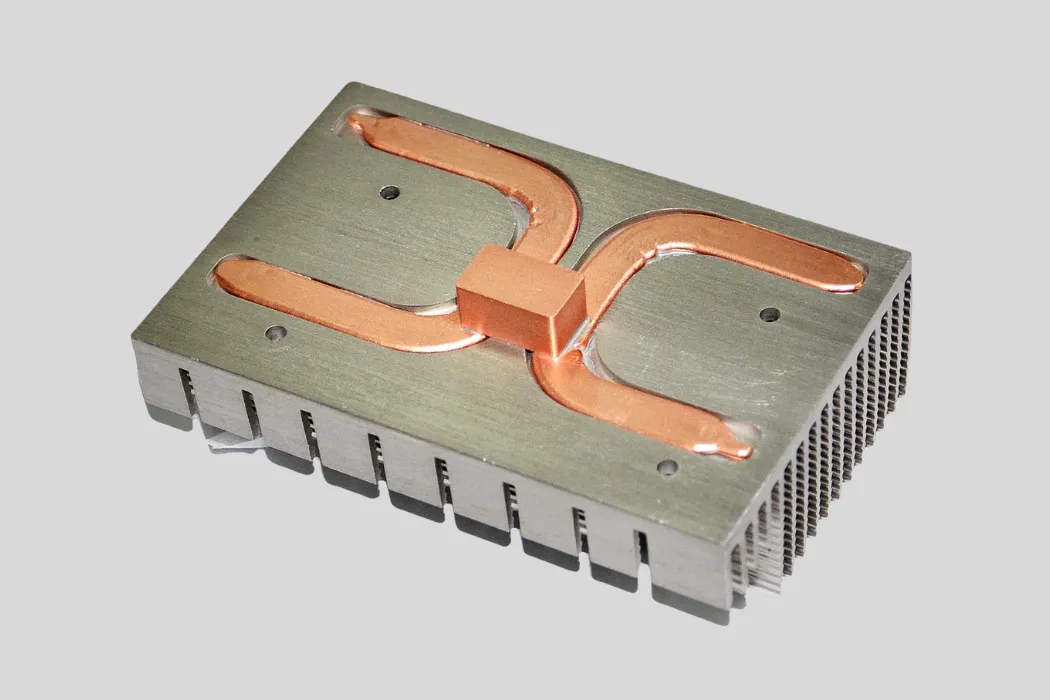

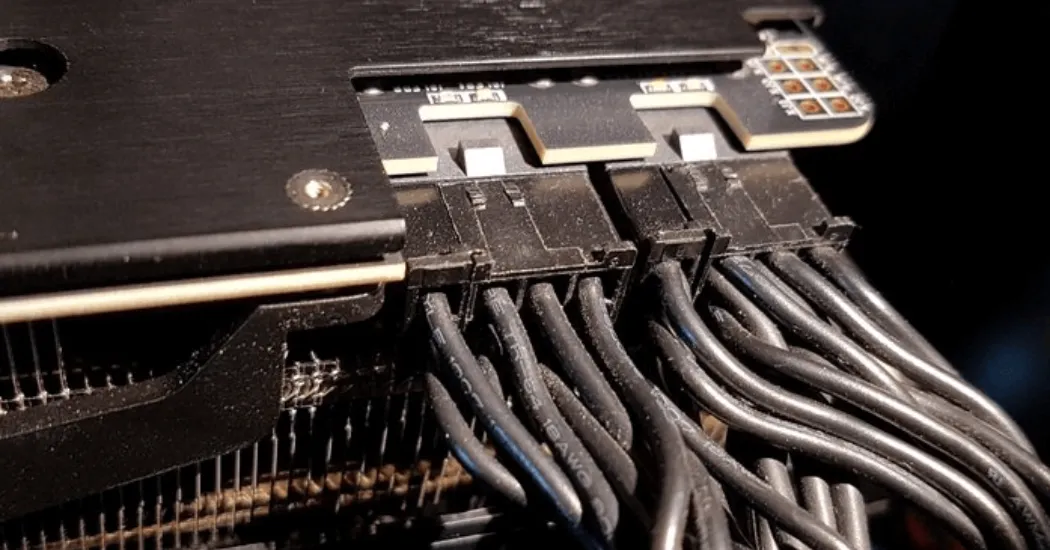

Step 4: Air Cooling vs. Liquid Cooling for High-TDP Components

TDP, combined with the real power limits (PL2/PPT), provides a clear indicator for when you need to graduate from air cooling to liquid cooling. While high-end air coolers can handle brief spikes up to around 200W, they struggle with sustained loads at this level.

As a general guideline, once a component’s peak and sustained thermal load pushes beyond the 200-250W range, a liquid cooling solution like a liquid cold plate becomes the superior engineering choice. It offers lower temperatures, quieter operation, and a more compact form factor, providing the necessary performance to cool today’s most powerful processors without compromise.

What Are the Future Trends Beyond TDP?

The concept of TDP is evolving. As processors become more complex and power-hungry, the industry is slowly moving away from this single, simplified number. The future of thermal design lies in more transparent power metrics, a holistic system-level approach to cooling, and the understanding that advanced thermal solutions are no longer just preventative measures—they are performance-enhancing components in their own right.

The Rise of More Transparent Power Metrics (PL1, PL2, PPT)

The industry is already shifting towards more honesty. Metrics like Intel’s PL1/PL2 and AMD’s PPT are becoming more prominent in technical documentation and reviews. This trend will likely continue, with less emphasis placed on the marketing-friendly TDP and more on the detailed power states that engineers actually need to design for. This transparency empowers engineers to create more effective and accurately specified thermal solutions from the outset.

The Shift Towards System-Level Cooling Design

The focus is expanding from simply cooling the CPU to managing the thermal health of the entire system. In a compact, high-power device, the heat from the CPU affects the temperature of the memory, the storage, and the power delivery components. The future of thermal design involves a holistic approach, using simulation to understand how all components interact and designing integrated cooling solutions that manage the entire thermal ecosystem, not just a single chip.

How Advanced Cooling Unlocks Higher Performance from the Same TDP

Here is the most exciting trend: a better cooling solution can effectively increase the performance of a processor. A superior custom thermal solution, like an FSW liquid cold plate from Walmate, can dissipate heat so efficiently that it allows a CPU to remain in its high-power boost state (PL2/PPT) for a much longer duration, or even indefinitely. This means that for the exact same chip, a better cooling system directly translates to faster, more sustained performance. Cooling is no longer just about preventing throttling; it’s about enabling a higher level of performance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What happens if my cooler’s TDP is lower than my CPU’s TDP?

Your CPU will almost certainly overheat under load. To protect itself, it will aggressively throttle, meaning it will drastically reduce its clock speed to lower the temperature. This will result in severe performance loss, stuttering, and potentially a system crash. It is crucial to use a cooler that meets or, ideally, exceeds the CPU’s thermal requirements.

2. Is a higher TDP CPU always better or faster?

Generally, a higher TDP indicates a higher performance potential, as the chip is designed to handle more power. However, it’s not the only factor. Architectural improvements mean a newer, lower-TDP chip can sometimes outperform an older, higher-TDP one. But within the same generation, a higher TDP almost always means more performance, provided you have adequate cooling.

3. Does undervolting change a component’s TDP?

No. The official TDP is a fixed specification from the manufacturer. However, undervolting (reducing the voltage supplied to the component) can lower the actual heat output and power consumption. This can allow the component to run cooler and potentially maintain its boost clocks for longer, effectively improving performance within the same thermal environment.

4. How do I find the real power consumption of my CPU, not just the TDP?

The best way is to look for the manufacturer’s detailed specifications, such as Intel’s “Maximum Turbo Power” (PL2) or AMD’s “Package Power Tracking” (PPT). Additionally, you can use hardware monitoring software like HWMonitor or HWiNFO64 to see the real-time package power draw of your CPU under different loads.

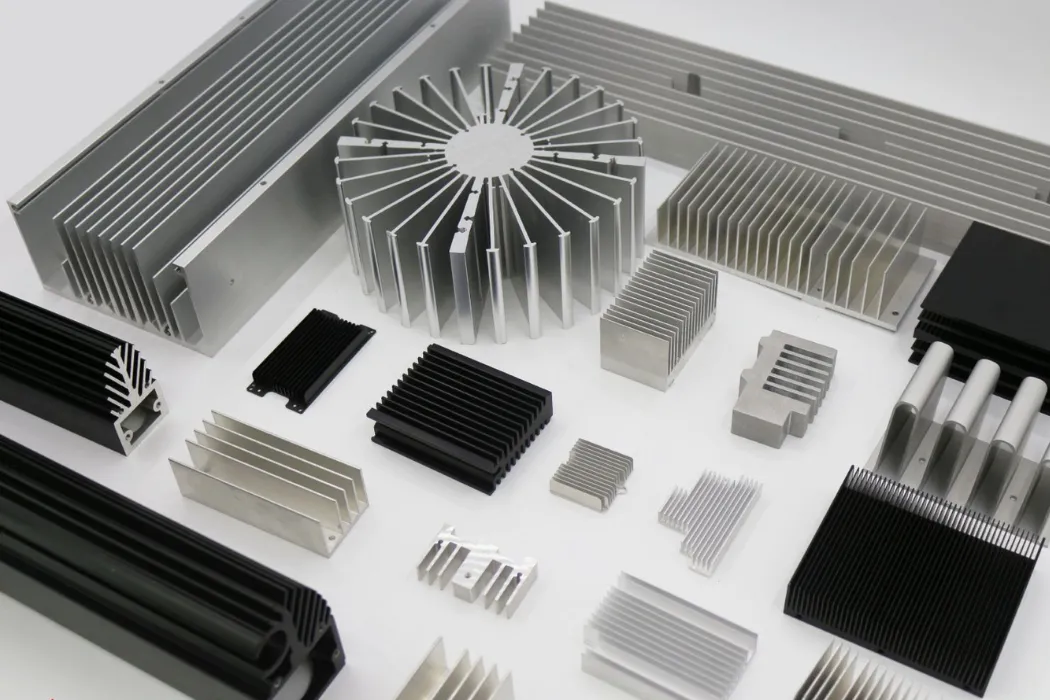

5. Why do two coolers with the same TDP rating have different performance?

TDP ratings on coolers are often a simplified marketing metric and not standardized across brands. Factors like the quality of materials (copper vs. aluminum), the number of heat pipes, fin density, fan quality, and overall design can lead to significant real-world performance differences, even if the “TDP rating” on the box is the same.

6. For a custom device, is it enough to just tell my thermal partner the TDP?

No, the TDP is only the starting point. To design an effective custom thermal solution, an expert partner like Walmate Thermal needs more information, including the peak power (PL2/PPT), the physical dimensions of the device, the chassis airflow characteristics, and the expected use case and ambient operating temperatures.

7. Do you need to consider TDP when choosing a power supply (PSU)?

Yes, but you should focus on the peak power draw (PL2/PPT), not the TDP, for both your CPU and GPU. You need a PSU with enough wattage to comfortably handle the maximum potential power draw of all your components combined, with some extra headroom for safety and efficiency.

8. Can a better thermal solution (like a liquid cold plate) lower my component’s TDP?

No, the TDP is a fixed value set by the chip manufacturer. However, a better thermal solution provides more “thermal headroom.” This allows the component to reach and sustain its high-power boost states more effectively and for longer periods, resulting in significantly better real-world performance from the exact same chip.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond the Label to True Thermal Design

Thermal Design Power is an essential starting point in a thermal conversation, but it is a dangerously incomplete metric for final engineering decisions. As we’ve seen, it’s a simplified label for a complex thermal reality, representing an average case, not the peak performance state where your product’s true value is demonstrated. Relying solely on TDP is a path to creating underperforming and unreliable products.

True thermal management requires looking beyond the label. It demands a deeper understanding of the real-world heat load, a consideration of peak power states, and a commitment to designing a solution that can handle maximum performance, not just “typical” use. This is the difference between adequacy and excellence.

When TDP isn’t enough, you need a partner who speaks the language of real-world thermal performance.

At Walmate Thermal, we go beyond datasheets. Our experts use advanced thermal simulation (CFD) and rigorous validation testing to design and manufacture custom thermal solutions—from heat sinks to liquid cold plates—that are guaranteed to handle your product’s true heat load.Contact our engineering team today for a quote, and let’s design a solution for performance, not just for a spec sheet.